Table of Contents

Climate change is primarily a problem of too much carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. This carbon overload is caused mainly when we burn fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas or cut down and burn forests.

There are many heat-trapping gases (from methane to water vapor), but CO2 puts us at the greatest risk of irreversible changes if it continues to accumulate unabated in the atmosphere. There are two key reasons why.

CO2 has caused most of the warming and its influence is expected to continue

CO2 has contributed more than any driver to climate change between 1750 and 2011.

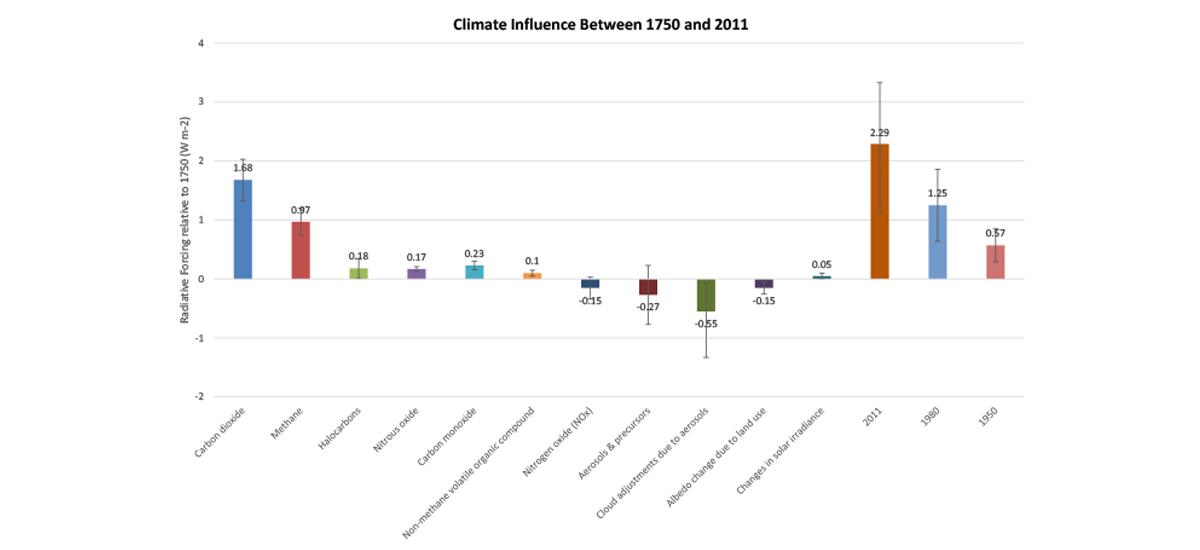

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a global climate assessment in 2013 that compared the influence of three changes to the environment resulting from human activity between 1750 and 2011: the emission of key heat-trapping gases and tiny particles known as aerosols, as well as land use change.

By measuring the abundance of heat-trapping gases in ice cores, the atmosphere, and other climate drivers along with models, the IPCC calculated the “radiative forcing” (RF) of each climate driver—in other words, the net increase (or decrease) in the amount of energy reaching Earth’s surface attributable to that climate driver.

Positive RF values represent average surface warming and negative values represent average surface cooling. In total, CO2 has the highest positive RF (see Figure 1) of all the human-influenced climate drivers compared by the IPCC.

Other gases have more potent heat-trapping ability molecule per molecule than CO2 (e.g. methane), but are simply far less abundant in the atmosphere.

CO2 sticks around

CO2 remains in the atmosphere longer than the other major heat-trapping gases emitted as a result of human activities. It takes about a decade for methane (CH4) emissions to leave the atmosphere (it converts into CO2) and about a century for nitrous oxide (N2O).

After a pulse of CO2 is emitted into the atmosphere, 40% will remain in the atmosphere for 100 years and 20% will reside for 1000 years, while the final 10% will take 10,000 years to turn over. This literally means that the heat-trapping emissions we release today from our cars and power plants are setting the climate our children and grandchildren will inherit.

What about water vapor?

Water vapor is the most abundant heat-trapping gas, but rarely discussed when considering human-induced climate change. The principal reason is that water vapor has a short cycle in the atmosphere (10 days on average) before it is incorporated into weather events and falls to Earth, so it cannot build up in the atmosphere in the same way as carbon dioxide does. However, a vicious cycle exists with water vapor, in which as more CO2 is emitted into the atmosphere and the Earth’s temperature rises, more water evaporates into the Earth’s atmosphere, which increases the temperature of the planet. The higher temperature atmosphere can then hold more water vapor than before.

Too much of a good thing: the carbon overload

Earth receives energy that travels from the sun in a variety of wavelengths, some of which we see as sunlight and others that are invisible to the naked eye, such as shorter- wavelength ultraviolet radiation and longer-wavelength infrared radiation.

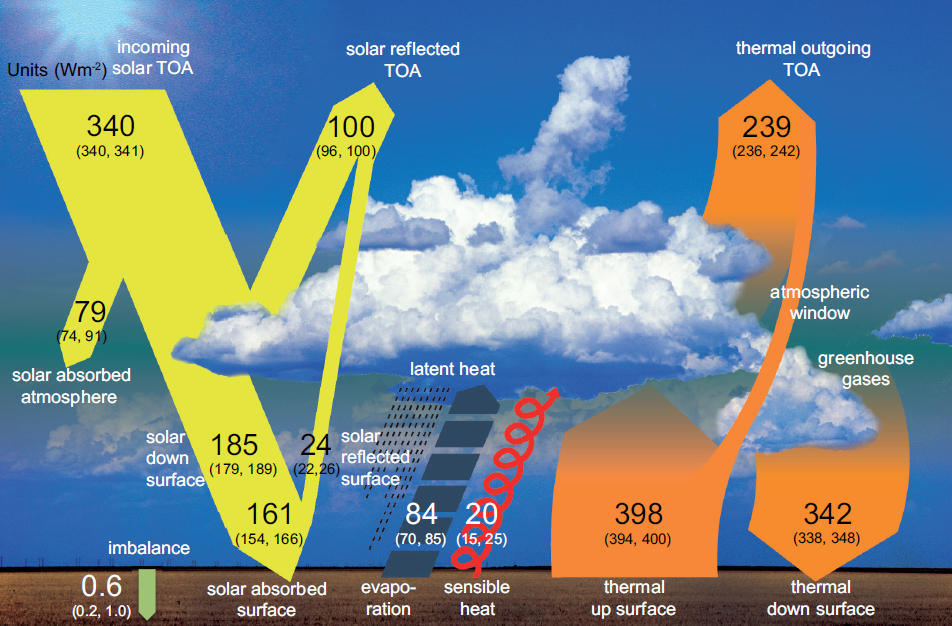

As this energy passes through Earth’s atmosphere, some is reflected back into space by clouds and small particles such as sulfates; some is reflected by Earth’s surface; and some is absorbed into the atmosphere by substances such as soot, stratospheric ozone, and water vapor (See yellow arrows in Figure 2 for relative proportions). The remaining solar energy is absorbed by the Earth itself, warming the planet’s surface.

If all the energy emitted from the Earth’s surface (orange “thermal up surface” arrow in Figure 2) escaped into space, the planet would be too cold to sustain human life.

Fortunately, as depicted in Figure 2 (orange “thermal down surface” arrow), some of this energy does stay in the atmosphere, where it is sent back toward Earth by clouds, released by clouds as they condense to form rain or snow, or absorbed by atmospheric gases composed of three or more atoms, such as water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O), and methane (CH4).

Long-wave radiation absorbed by these gases in turn is re-emitted in all directions, including back toward Earth, and some of this re-emitted energy is absorbed again by these gases and re-emitted in all directions.

The net effect is that most of the outgoing radiation is kept within the atmosphere instead of escaping into space.

Heat-trapping gases, in balanced proportions, act like a blanket surrounding Earth, keeping temperatures within a range that enables life to thrive on a planet with liquid water.

Unfortunately, these gases—especially CO2—are accumulating in the atmosphere at increasing concentrations due to human activities such as the burning of fossil fuel in cars and power plants industrial processes, and the clearing of forests for agriculture or development.

As a result, the insulating blanket is getting too thick and overheating the Earth as less energy (heat) escapes into space.

Long-term perspective

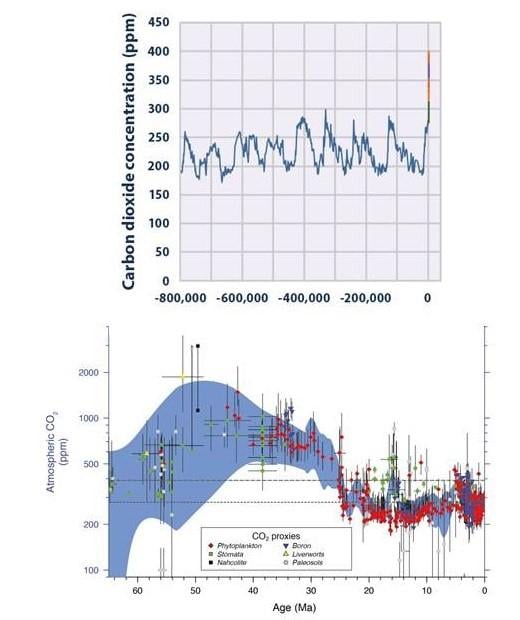

Antarctic ice core records vividly illustrate that atmospheric CO2 levels today are higher than levels recorded over the past 800,000 years (see Figure 3).

Atmospheric CO2 levels rose 40 percent between 1750 and 2011. (In 2013, atmospheric CO2 levels surpassed 400 million parts per million for the first time in human history.) Half of human-related CO2 emissions occurred only in the last 40 years. CO2 (and other gases emitted from industrial and agricultural sources) trap heat in the atmosphere, so it is no surprise that we are now witnessing an increase in global average temperature.

In the same way that CO2 emitted long ago is now contributing to the changes in climate we are already experiencing today, the emissions we are currently releasing will help determine the climate future our children and grandchildren experience.