Fires across the West are threatening water supplies for millions of people—particularly in areas hard hit by climate change, like California.

At a basic level, the connection between wildfires and water is intuitive: fires start more easily, burn more intensely, and spread faster when it’s dry.

That’s bad news, because climate change is increasing the risk of drought in certain regions. It’s particularly pronounced in the western United States, where heatwaves, megadroughts, and earlier snow melt are priming forests for wildfire. In fact, western forests are now roughly 50 percent drier due to climate change.

Importantly, it’s not always the case that climate change reduces the amount of water an area receives. But it’s changing how, when, and in what form the drought-prone western United States gets its water—with profound consequences for watersheds, wildfires, and the communities downstream.

Watersheds and wildfire

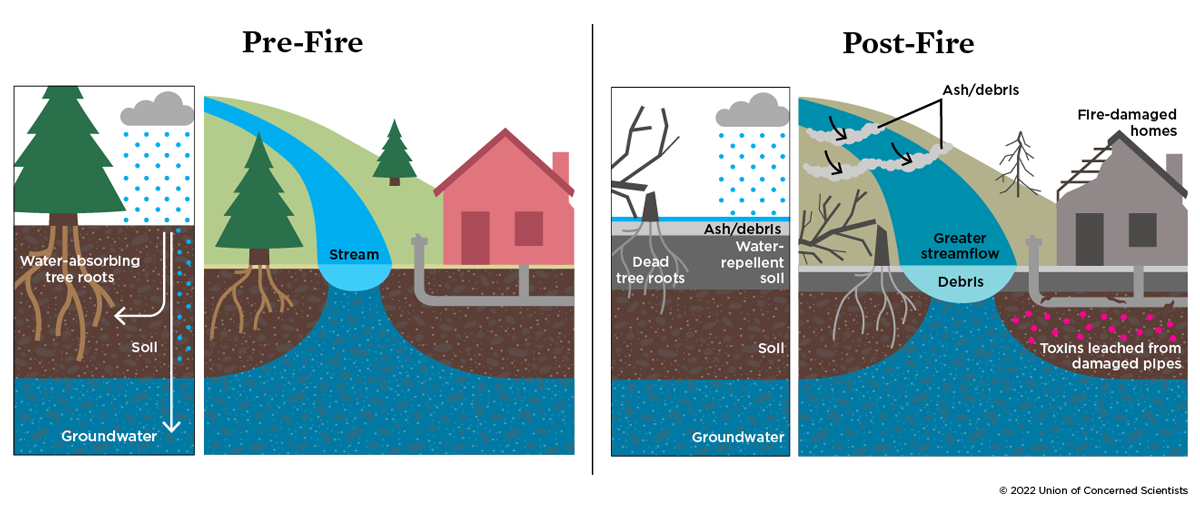

Every drop of water we use comes from a watershed. Watersheds have two distinct parts: surface water, carried in streams, rivers, and lakes, and groundwater, stored in underground aquifers.

Watersheds rely on a range of plants and organisms. For example, healthy soils help filter water, breaking down organic material and dissolving harmful compounds. And water that can seep through healthy soils adds to our groundwater storage.

Wildfires disrupt that. Fires, especially high-intensity fires, remove vegetation and roots, which destabilizes the ground and produces runoff. Soil is less able to absorb or filter water after a fire, and ash can act like a plastic sheet, encouraging even more runoff.

All this runoff leads to floods, landslides, and debris flows. It can also mean changes in how much water gets absorbed and stored underground—potentially a major problem in California, which relies on groundwater to sustain itself during droughts.

Wildfires also release toxic substances into watersheds, especially when they burn things like cars, homes, and infrastructure. Tragically, public drinking water systems commonly suffer elevated concentrations of toxic compounds like nitrates, benzenes, and arsenic in areas downstream of large wildfires.

Solutions

If we zoom out, we see climate change increasing the size and severity of wildfires. We see wildfires kicking off a cascade of other problems, including reduced water quality and quantity. And we see these problems already happening in areas like California that struggle to meet the water needs of people, ecosystems, agriculture, and other industries.

What can be done? Better forest and fire management techniques, inspired by Indigenous practices and focused on limiting the severity of wildfires, can help. Certain post-wildfire treatments, such as salvage logging and replanting, may help in certain contexts. And community investments in things like heat-resistant pipes or better filtering at municipal water treatment plants can help safeguard against contamination.

But until we tackle the root causes of climate change, the relationship between wildfire and water will only worsen. You can help.

Wildfire & Water in the Western United States

Infographic: Wildfires and Climate Change

Troubled Waters