As the 2020 election approaches and more people are choosing to vote by mail, reliable mail service is urgently needed across the country—but the evidence shows that people are having problems receiving mail, which could threaten their ability to vote.

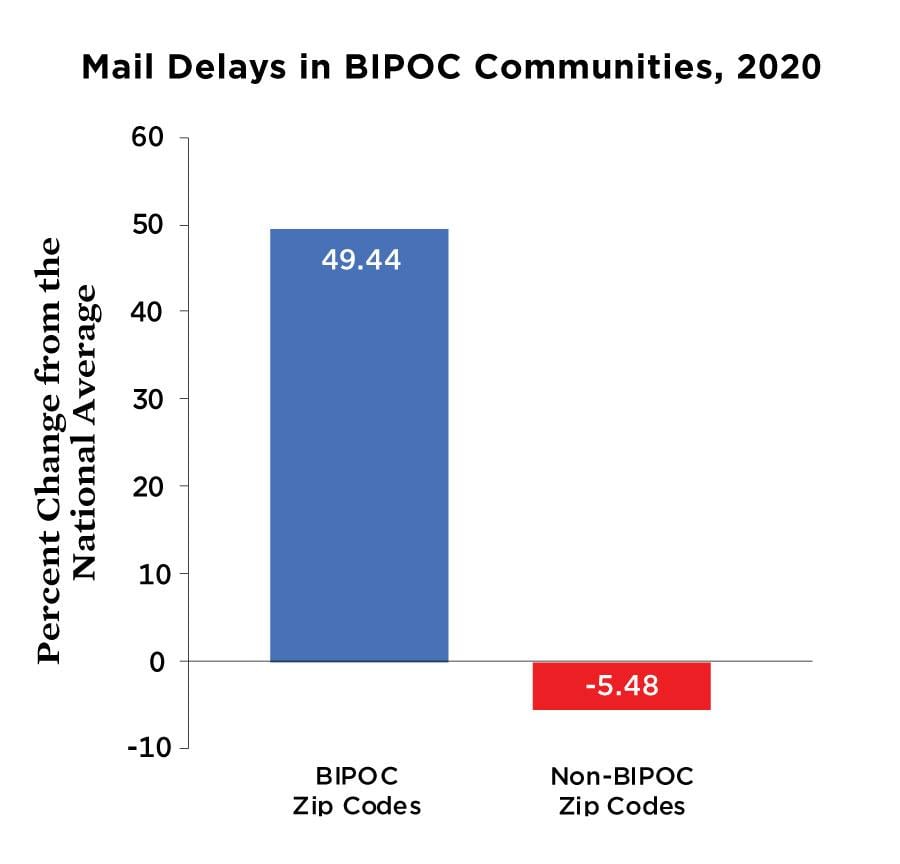

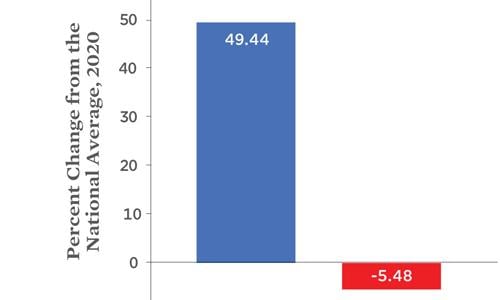

New analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists, based on data obtained from Freedom of Information Act requests, shows troubling trends. The total number of mail delivery complaints nationwide has increased since March 2020. And in zip codes where 45 percent or more of the people are Black, Indigenous, or other people of color, the average number of complaints about mail delays from January to July 2020 is almost 50 percent higher than the average for all US zip codes.

Signed, Sealed, but Not Delivered

Complaints about delayed mail from the United States Postal Service (USPS) have increased this year, especially in communities with more Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color (BIPOC), according to new research by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). As the 2020 election approaches and many more people vote by mail to stay safe during the COVID-19 pandemic, the public urgently needs reliable mail service—but evidence suggests that people are having problems receiving mail, which could threaten their ability to vote.

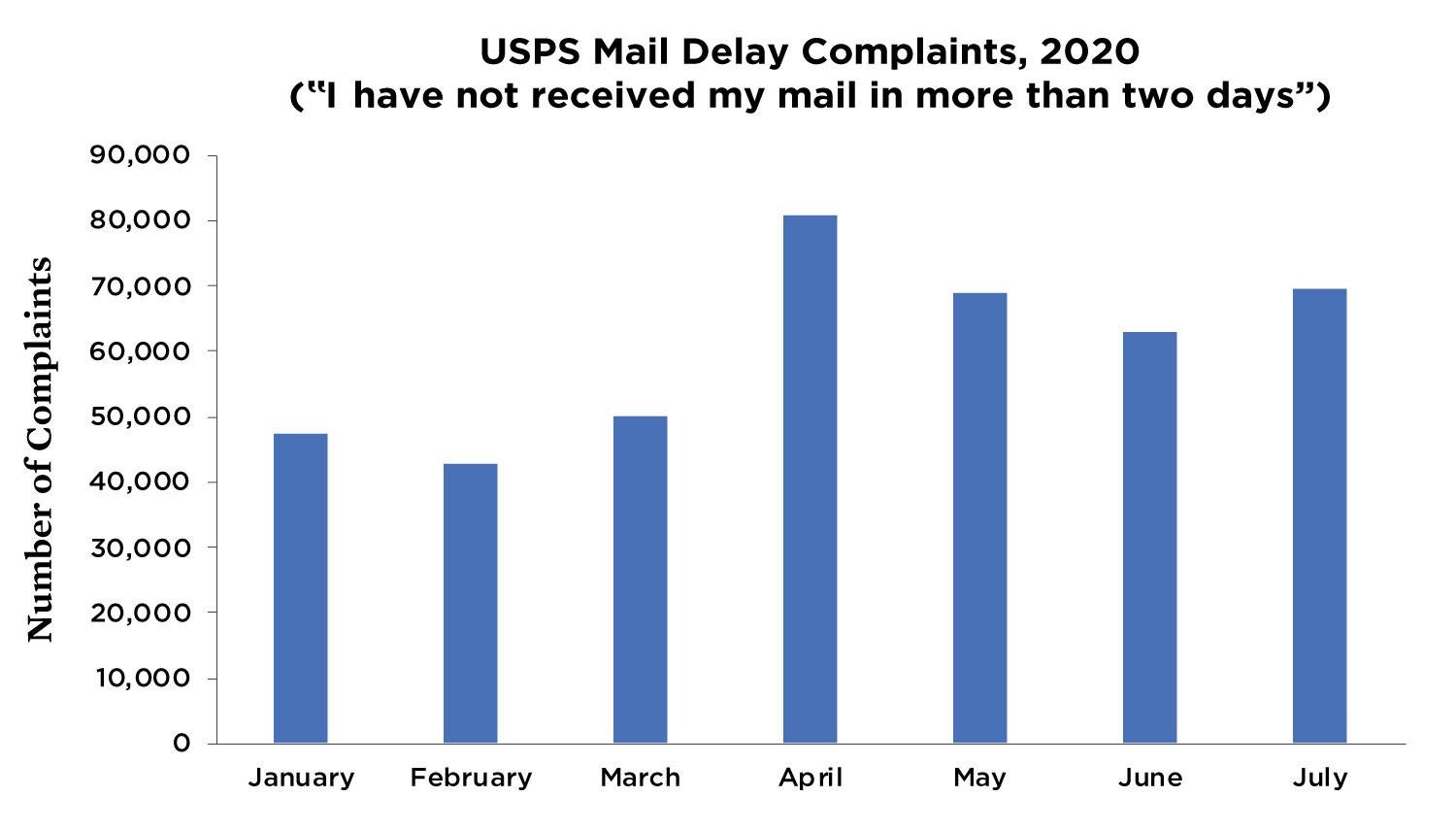

Through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, UCS obtained data on inquiries and complaints submitted by USPS customers from January to July 2020. We focused on complaints from customers who had not received mail for more than two days, which sharply increased in mid-March, reaching an unusually high level that persisted through July (the last month of available data).

Findings

- In January and February 2020, the USPS received an average of about 9,000 complaints per week from customers who had not received mail for more than two days. By April, this weekly average had jumped to 16,000 and has not dropped below 12,000 since.

- The data suggest mail delays could be disproportionately affecting communities of color. When controlling for population, people in zip codes where more than 45 percent of the population are BIPOC submitted 50 percent more mail delay complaints than other zip codes.

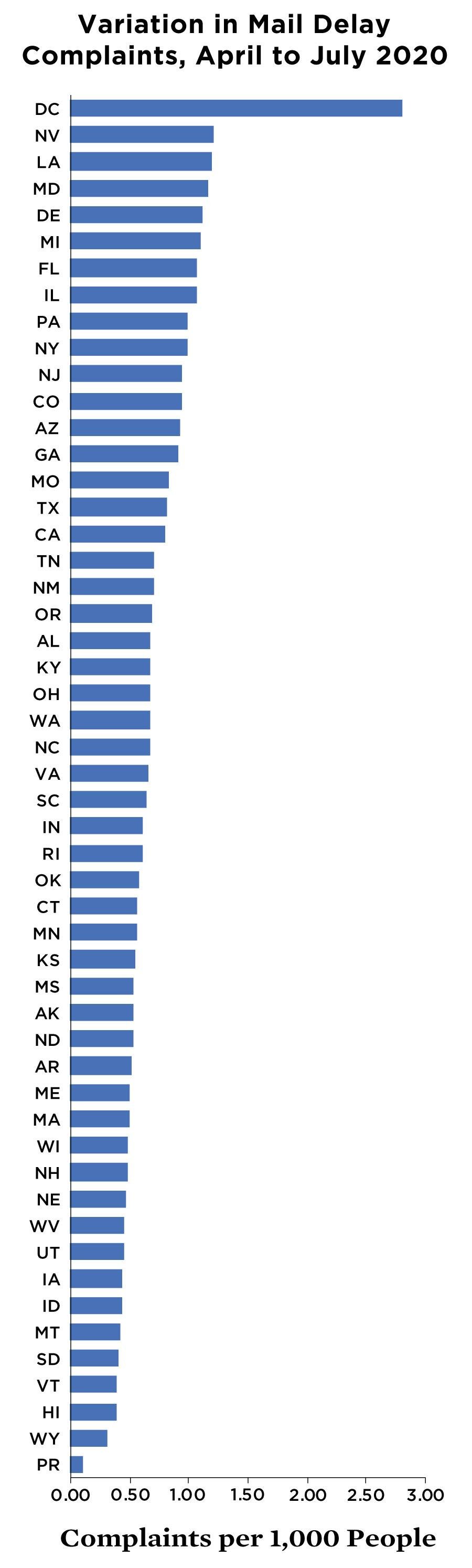

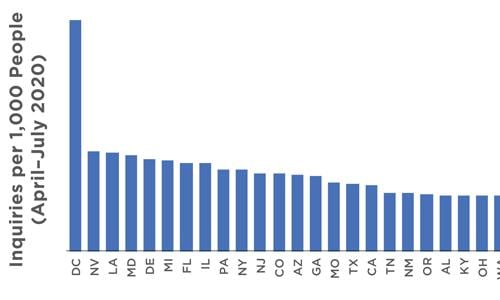

- From April to July 2020, Washington, DC, saw the highest number of mail delay complaints: 2.8 per 1,000 people. Nevada and Louisiana followed, each with about 1.2 inquiries per 1,000 people.

Mail delays leading up to the general election threaten the democratic process

For nearly 250 years, the USPS has been a vital public service. Its reach is immense: In 2019, postal workers traveled 1.34 billion miles to deliver nearly 143 billion pieces of mail around the globe. Its employees number more than 630,000, and it handles 48 percent of the world's mail.

This year, the USPS must serve an additional, extraordinary role. Millions of people will cast ballots in local, state, and federal elections this November, and—with more than 215,000 people dead from COVID-19 and health officials urging the public to practice social distancing—many will choose to vote by mail. With at least 75 percent of US voters eligible to vote by mail this year, experts expect between 80 million and 100 million ballots to be mailed.

There are real reasons to worry. The recently appointed postmaster general, Louis DeJoy, instituted far-reaching changes to the USPS that experts say could threaten its ability to handle election-related mail. He cracked down on worker overtime and late mail deliveries, forcing postal workers to leave mail behind, and ordered the decommissioning and even dismantling of mail-sorting machines—more than 700 this year alone. Although pushback from at least 20 states and the public, as well as rulings by four federal courts, led DeJoy to suspend these changes, the damage that has already been done could be felt during the election and for months or years afterward.

The USPS was under strain even before this summer's slew of cost-cutting changes. Since a 2006 law imposed new burdens, the USPS has remained in debt despite finishing each year with revenue surpluses for most of the last decade. This strain, coupled with the surge in mail-in voting, has already affected elections: during the 2020 primaries, at least 9,000 absentee ballots were never sent to voters who requested them in Wisconsin, and many that were sent never reached voters.

These trends could prove challenging for voters in the 2020 general election. Our findings reveal that mail delays have increased since the start of the pandemic, especially in communities of color. This disparity may have existed before the pandemic and the USPS's recent operational changes, but it still poses a threat to how ballots will be delivered, returned, and counted reliably come November.

Members of underserved communities already face enormous barriers to voting: they have been disenfranchised through gerrymandering, been purged from voter rolls, blocked from early voting, and saddled with restrictive ID laws. Younger, Black, and Latino voters also have their mail-in ballots rejected at higher rates. A disempowered USPS could further entrench these disparities, which research has shown can harm public health.

Other teams are investigating mail delays as well. Where UCS relied on raw numbers of mail delay complaints nationwide, the New York Times calculated the percentage of mail delivered on time in several US cities. Both analyses found that mail delays increased over the summer. The Times also found that delays spiked in July, when the postmaster general instituted his operational changes. Collectively, these analyses, while likely to change as more data are received, paint a troubling picture.

The USPS has provided jobs and a lifeline to government services for millions of people regardless of race or income, including for rural communities and those who receive necessities like medicine through the mail. It is also a popular public good, earning approval from 90 percent of people in the United States. This year and in future years, the USPS must be well funded, well resourced, and championed by our elected officials as it works to uphold the democratic process—for all of us, equally.

Methodology

UCS obtained USPS data on mail delay complaints by postal code via several FOIA requests. These data were organized by date and zip code of the mail delivery facility. Data on postal customers' zip codes were not available.

We obtained population and race data from the US Census Bureau by Zip Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA). We then calculated an area-weighted sum to assign this population data to the postal zip code areas of interest. For example, if a ZCTA had 100 people and 50 percent of that ZCTA fell within a zip code boundary, we assumed 50 people from that ZCTA live in the zip code of interest.

As postal codes are drawn for the purpose of mail delivery and do not necessarily account for the size of the population in each zip code, we needed to standardize the numbers to compare them. Ideally, we would standardize by total mail volume, but these numbers were not available at the time of analysis due to delays in FOIA request responses from the USPS. For this reason, we divided the number of inquiries by the population of the zip code, in order to account for population differences that could explain the differences in total complaints across zip codes We then multiplied the resulting decimal by 1,000, which gave us the number of complaints per 1,000 people.

To calculate the percent change from the US average, we subtracted the US average from the demographic group average and then divided by the US average. We multiplied this number by 100 to give us a percent change value.

Since starting this analysis, we have requested additional records from the USPS. As we receive more data, we will update and expand our results.

Downloads

Citation

Mackinney, Taryn, Casey Kalman, Genna Reed, Michael Latner, and Gretchen Goldman. 2020. Signed, Sealed, But not Delivered: Communities of Color Face Higher USPS Mail Delays. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists. https://www.ucsusa.org/node/13823