One billion people lack adequate access to food. To address this, we need smart changes to the food system—not false solutions.

For years, discussions of world hunger have contended with an ugly, persistent, and deeply problematic idea: there are simply too many people to feed in the world. In the 1960s, Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich claimed in his book The Population Bomb that the world would run out of food, water, and other resources without steps to control population. And as recently as 2019, Fast Company produced a video, “Why having kids is the worst thing you can do for the planet,” based on a study reporting that having children increases resource use, including those used to grow food, more than any other human activity.

Such narratives may cause some to ask whether population control is a necessary solution to ensure that people now and in the future have the food they need. But as rational as that approach may appear, population is not the problem that deserves our focus. And it is certainly not the solution.

The top issue: food security

When a person has at all times physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life, they’re said to have food security. Achieving food security for everyone is a major goal of global health and humanitarian efforts.

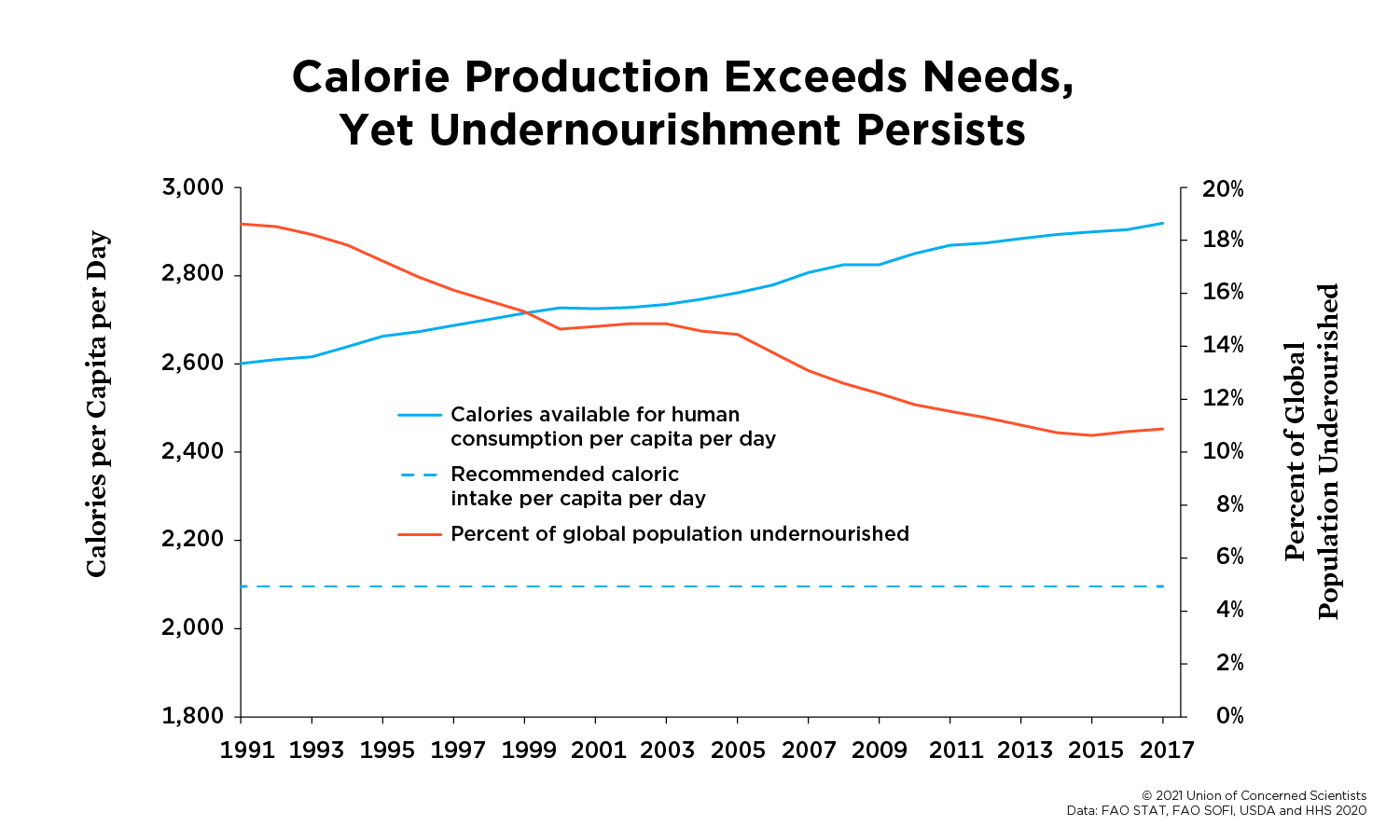

But food security is about more than just total food production, which is why simply focusing on total food production, food availability, and population growth to achieve it is flawed. In fact, today’s farmers produce more than enough calories for all 7.8 billion people on earth. Yet nearly one billion people don’t have enough food to eat. For even more, a nutritionally or culturally appropriate diet is out of reach.

Food insecurity is caused by systemic societal and distributional issues such as poverty, underemployment, racism, and other social and economic inequities, many of which can be resolved or mitigated with the right policies and legislation. The world’s dominant food and farm systems also damage the environment in ways that may reduce the amount of food that can be produced in the future.

For example, estimates suggest that agriculture for food, feed, fiber, and fuel accounts for around 70 percent of global freshwater use, 12 percent of the world's heat-trapping emissions, and a significant share of deforestation. Further, many agricultural practices employed today degrade soil, which makes farmland less productive and more vulnerable to flooding and drought.

Clearly, just boosting total food production won't ensure food security. So what’s needed?

The wrong answer: population control

When people think of hunger and other food security issues as being meaningfully connected to population size, they may also see population control as a viable solution. It is not and here is why.

Coercive limits on reproductive choices as a means to ensure that all people have the food they need are inappropriate, ineffective, and dangerous. Prohibiting the decision to freely and responsibly choose how many children one can have, and when, violates basic human rights and is reflective of anti-democratic governments, eugenics, and white supremacy.

With this in mind, understanding food security as being integrally related to economic and social systems—and not just food supply—is vital for ensuring all people are nourished, now and in the future.

Solutions

It's true that the global population is growing and that there will be increasing pressure on agriculture to meet dietary needs. But research points to several ways to ensure food security for current and larger global populations without population control measures. These include, but are not limited to, increases in healthy food production and availability through improved farming practices and systems, adoption of systems that preserve natural resources and biodiversity, shifts in crops and diets, and reduced waste across the supply chain.

Importantly, some approaches to increasing food availability can have unintended consequences. For example, the Green Revolution spurred a tripling of cereal crop production, alleviating poverty and food shortages in many low-income countries. But at the same time it also damaged or left behind many communities and had major ecological consequences. Thus, an inclusive, systems-based perspective of agriculture is essential to addressing food security. A systems-based perspective of agriculture is one that considers how changes in agriculture would impact the food system as a whole, including the natural resources that agriculture relies on, as well as the communities that contribute to and rely on agriculture.

This inclusive, systems-based perspective also means addressing the root causes of food insecurity and putting in place evidence-based government programs, since these issues cannot be resolved in the short term. To start, we need to address the racism and inequities that cause food insecurity. We also need to secure living wages for all people, including the very people who are essential to our food system. Additionally, policies and incentives that would allow people without financial resources to actually have access to the foods that are available, such as the very successful Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in the United States, can also help to alleviate food insecurity. Ensuring that domestic and international economic and political systems are addressing the roots of food insecurity issues, such as when food prices go awry, is also crucial.

It also means building food and farm systems that can adapt and remain resilient in the face of climate change. Policies can help farmers adopt practices that reduce heat-trapping emissions, protect our soil, air, water, and biodiversity, and buffer them from droughts, floods, and other extreme weather events that are becoming more frequent because of climate change.

Individuals can shift to more plant-centered diets, which not only helps the climate and environment, but also has health benefits. Policies can also encourage people to eat less meat and other animal products. These shifts, combined with those needed to reduce natural resource use by the agricultural sector, can help ensure that agriculture can manage the challenges that lie ahead.

So, if you hear someone suggest that global population growth is threatening food security now and in the future, tell them this: we must reject population control and advocate for meaningful systemic changes to how we produce, distribute, and consume food. In fact, doing both is essential.

UCS understands and appreciates that there are many groups doing valuable work on reproductive rights and women’s rights from a justice-centered perspective. We have great respect for that work. This webpage is intentionally centered on the food security dimensions of the population issue, given the focus of our work and expertise.