Scientific expertise is fundamental to the ability of many federal agencies to fulfill their missions. Agency scientists inform decisions that keep our air and water clean and our food safe, track disease outbreaks and ensure that we have effective responses, and tackle pressing scientific issues like climate change.

It is critically important that our federal agencies have the scientific capacity they need to fulfill their science-based missions and protect the public. A loss of expert scientists means a loss of scientific research and slower progress on critical issues of public health and safety.

The Trump administration attacked science, federal scientists, and their work on an unprecedented scale, and this pattern of attacks damaged our nation’s science capacity. Here, we provide analyses showing the number of scientists lost or gained across and within science-based federal agencies under the Trump administration.

The Federal Brain Drain

Scientific expertise is fundamental to the ability of many federal agencies to fulfill their missions. Agency scientists inform decisions that keep our air and water clean and our food safe, track disease outbreaks and ensure that we have effective responses, and tackle pressing scientific issues like climate change. It is critically important that our federal agencies have the scientific capacity they need to fulfill their science-based missions and protect the public. A loss of expert scientists means a loss of scientific research and slower progress on critical issues of public health and safety.

The Trump administration attacked science, federal scientists, and their work on an unprecedented scale. We documented more than 180 instances of political interference in science under the Trump administration, and multiple surveys have indicated that federal scientists’ morale reached an all-time low during these years.

This pattern of attacks also damaged our nation’s science capacity. For example, the US Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service and National Institute of Food and Agriculture lost 75 percent of its employees when the Trump administration hastily relocated these offices to Kansas City, Missouri. The resulting “brain drain” has delayed the completion of dozens of studies on a range of issues including veterans’ food security, international trade markets, and the opioid epidemic’s impacts on rural communities.

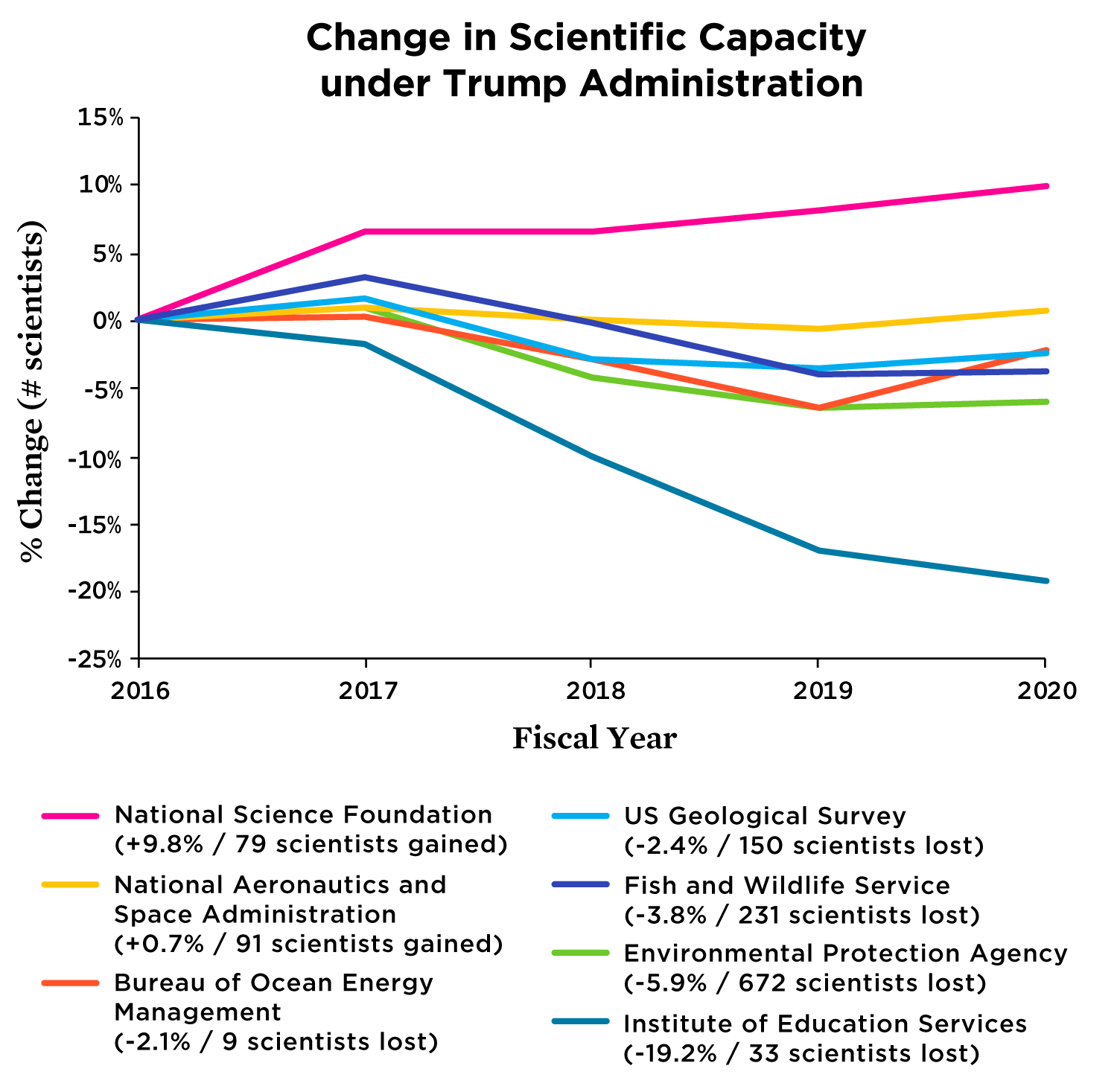

Here, we provide analyses showing the number of scientists lost or gained across and within science-based federal agencies under the Trump administration. Some agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), lost a significant number of scientists, while others, such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), saw an increase.

To obtain data for this analysis, we submitted Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to federal agencies with significant scientific capacity, asking for personnel and attrition records going back many years. We used the datasets we received, in conjunction with Office of Personnel Management (OPM) job series, to analyze trends in staffing by fiscal years and quarters, job grades, job series, and other metrics.

For the purposes of this study, we define “scientists” as anyone belonging to a job series that involves some level of scientific training or expertise, including but not limited to research, operations, modeling, inspection and oversight, and science policy. We identified these positions using the series codes and names of the OPM Handbook of Occupational Groups and Families, Part I (White Collar Occupational Groups and Series).

The data are organized by fiscal year (FY), rather than calendar year. Each fiscal year begins in October: the first quarter (Q1) is October to December; Q2 is January to March; Q3 is April to June; Q4 is July to September. We averaged the four FY quarters to yield the number of scientists for each year; US Geological Survey (USGS) quarters are represented by the last pay period of each.

Scientific Capacity across Federal Agencies

In our investigation, we found:

- The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) lost 6 percent of its scientific staff from 2016 to 2019 (a loss of 28 scientists) but gained 19 scientific experts in the last year.

- The NSF saw the largest gain of all agencies investigated, with a nearly 10-percent increase in scientific staff (an increase of 79 scientists).

Environmental Protection Agency—A Case Study

Given its significant loss of scientific capacity, we took a deeper look into the EPA. We found:

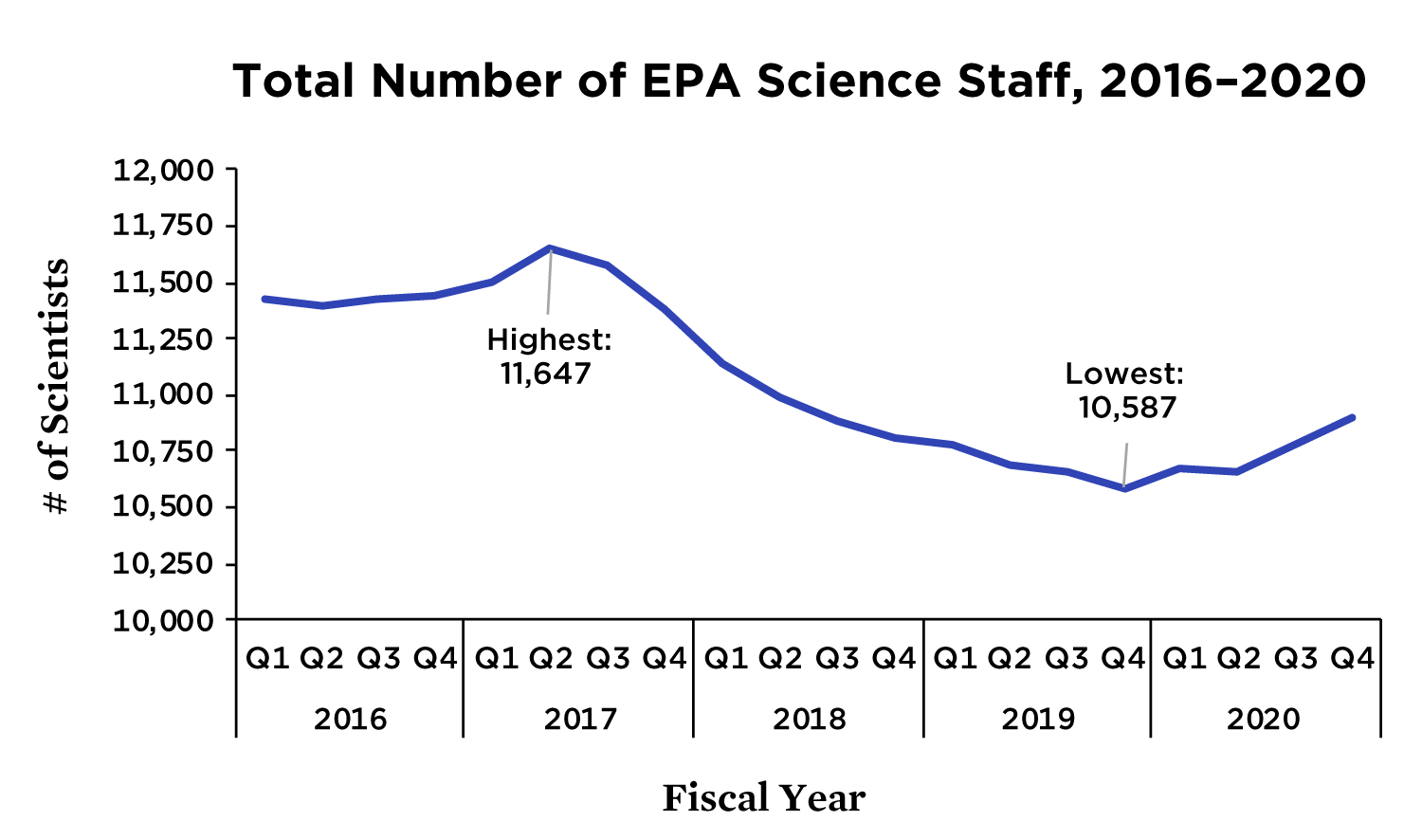

- The EPA lost more than 1,000 scientists between its highest reported number of scientists in Q2 of 2017 and its lowest reported number of scientists in Q4 of 2019.

- On average, the EPA lost about 219 scientists per year between 2016 and 2020.

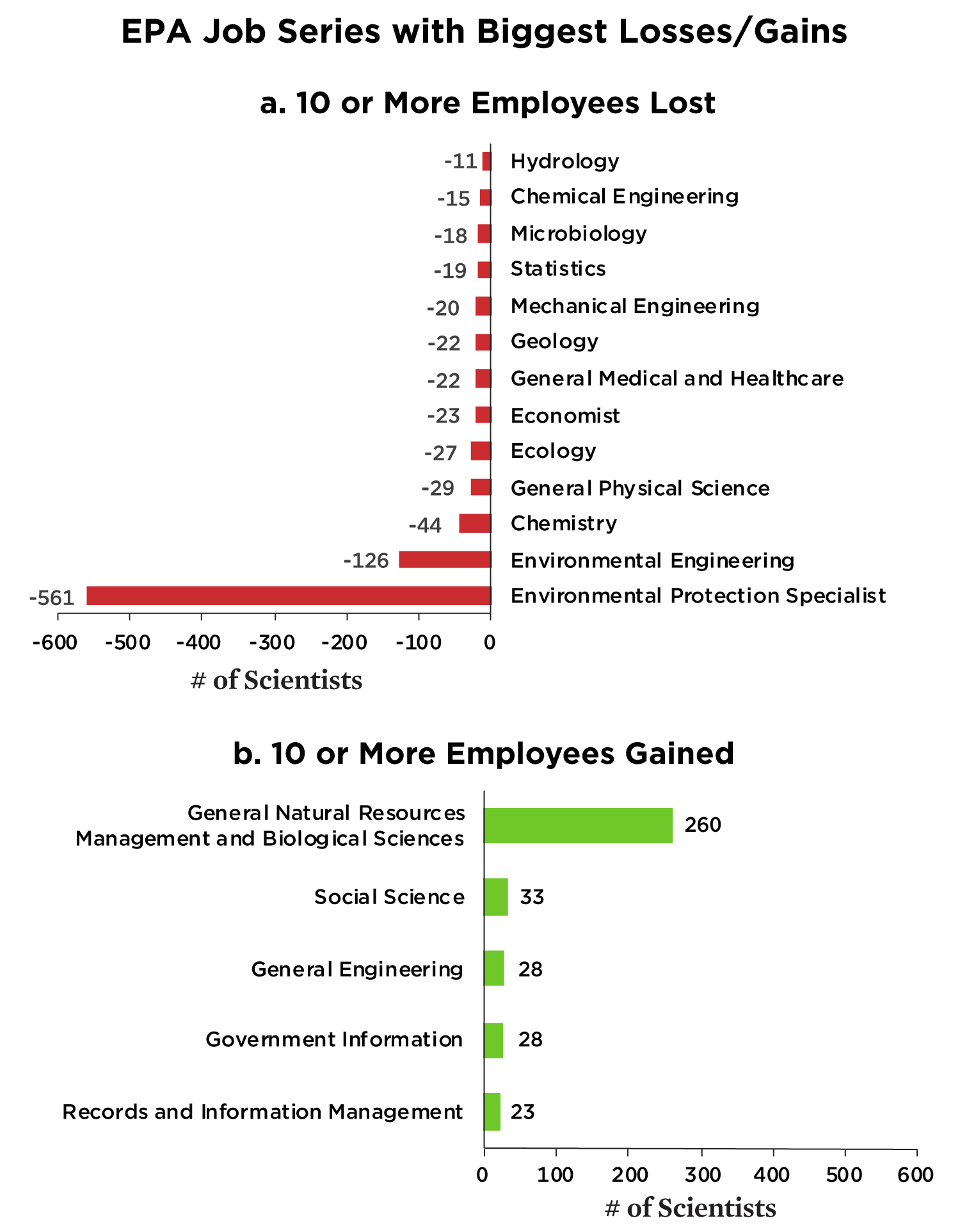

- Overall, the EPA saw increases in some job series, but significant losses in far more.

- The EPA lost more than 500 environmental protection specialists, a 24 percent decline. Their duties include working to protect or improve environmental quality, control pollution, remedy environmental damage, or ensure compliance with environmental laws and regulations.

- The agency also saw a loss of more than 100 environmental engineers on average—a 7 percent decline. These scientists plan and design environmental systems to provide clean water and air; identify and analyze substances or organisms that degrade the aquatic and soil environment; and measure, analyze, and describe air and water resources.

- The EPA also lost scientists in smaller series. For example, the EPA lost 12 hydrologists, 22 geologists, and 18 statisticians—about a third of jobs in each series. The EPA also lost 18 microbiologists (nearly 1 in 4 microbiologists at the EPA), and 27 ecologists (1 in 5).

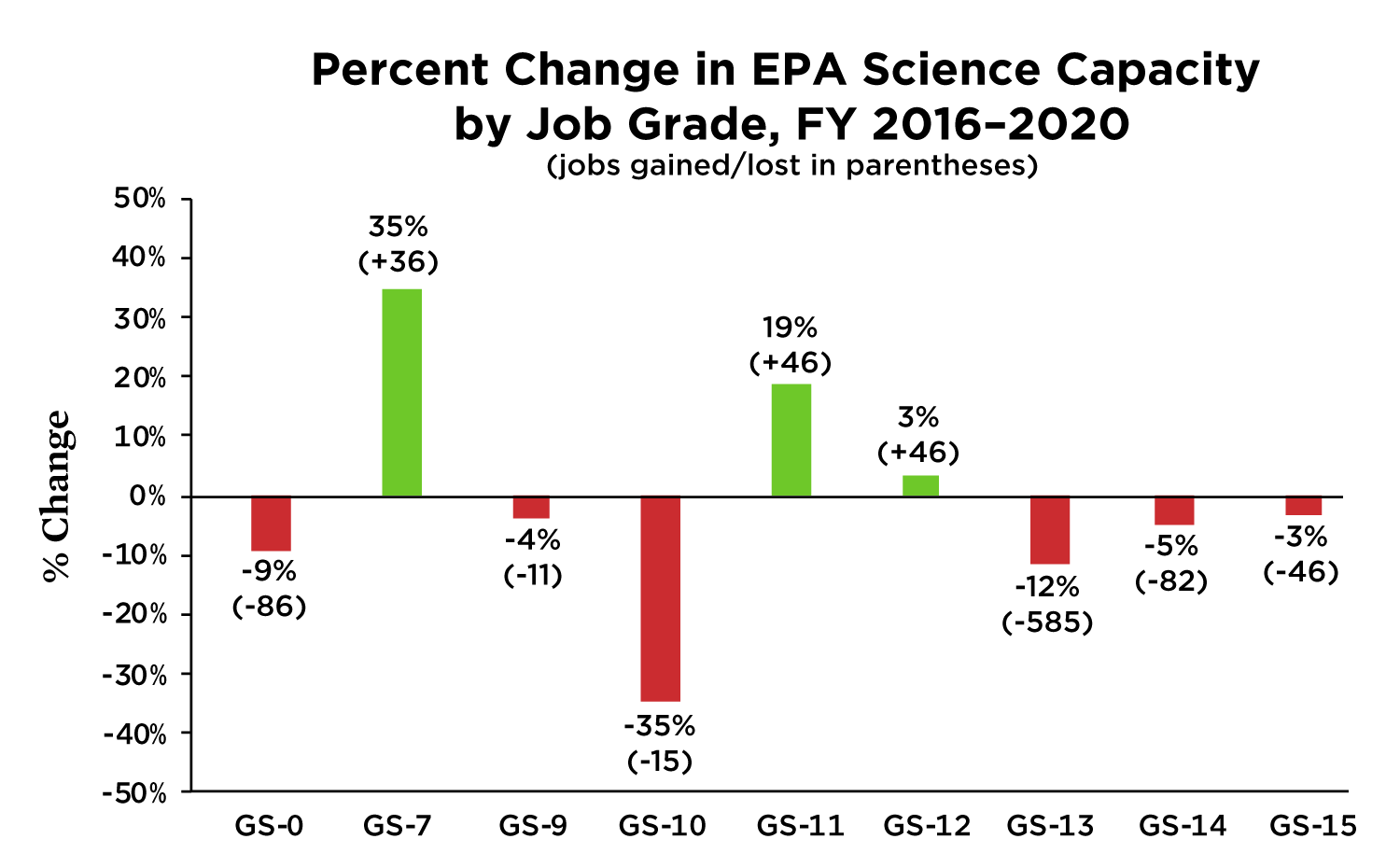

- More scientists were lost at lower grades than at higher grades between 2016 and 2020. Scientists at GS-14 and GS-15 levels only lost 3 to 5 percent of staff, whereas scientists at the GS-10 level lost 35 percent. Typically, the more experience and/or training, the higher the grade, so this may mean the EPA has fewer junior scientific staff to ascend in the agency.

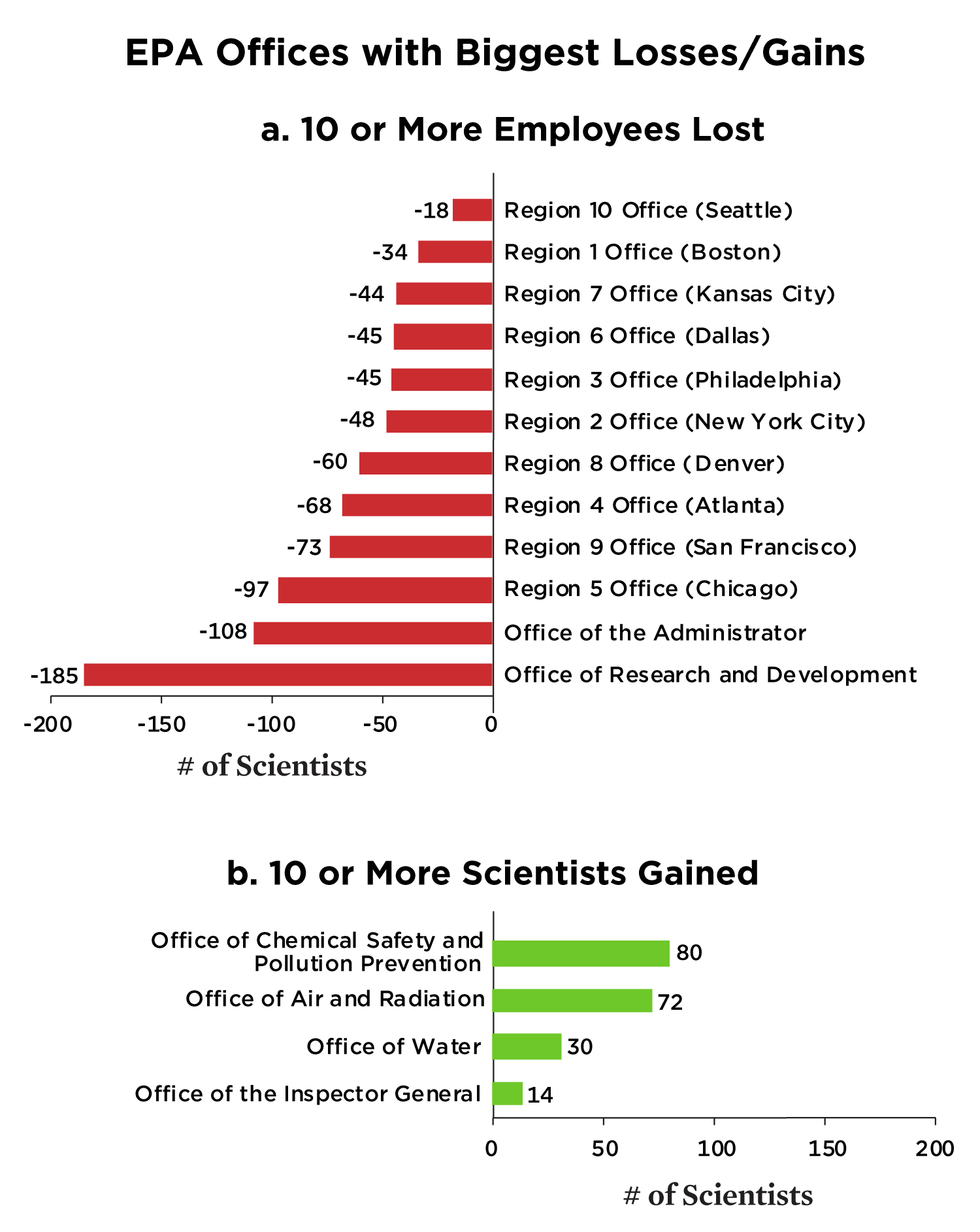

- Loss of scientists was widespread across programmatic and regional offices (Figure 5).

- All regional offices lost scientists under the Trump administration, with regions 2 and 9 losing 8 and 14 percent of their scientific staff, or 84 and 79 employees, respectively.

- The Office of Research and Development, the EPA’s research arm, lost more than 12 percent of its scientific staff (185 staff total) from 2016 to 2020.

Offices that were merged or renamed are not included in the figures above. In Q4 2016, the Obama administration EPA changed the name of the Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response (OSWER) to the Office of Land and Emergency Management (OLEM). In FY 2018, the Office of Administration and Resources Management (OARM) and the Office of Environmental Information (OEI) merged into the new Office of Mission Support (OMS).

Capacity Losses and Morale

The Trump administration’s attacks on science created a work environment in which many scientific experts reported low morale. The administration’s open disdain for science may have deterred scientists from seeking positions at the EPA and other agencies or discouraged current federal scientists from filling the positions of senior scientists who left for reasons such as early retirements, buyouts, or sustained hiring freezes.

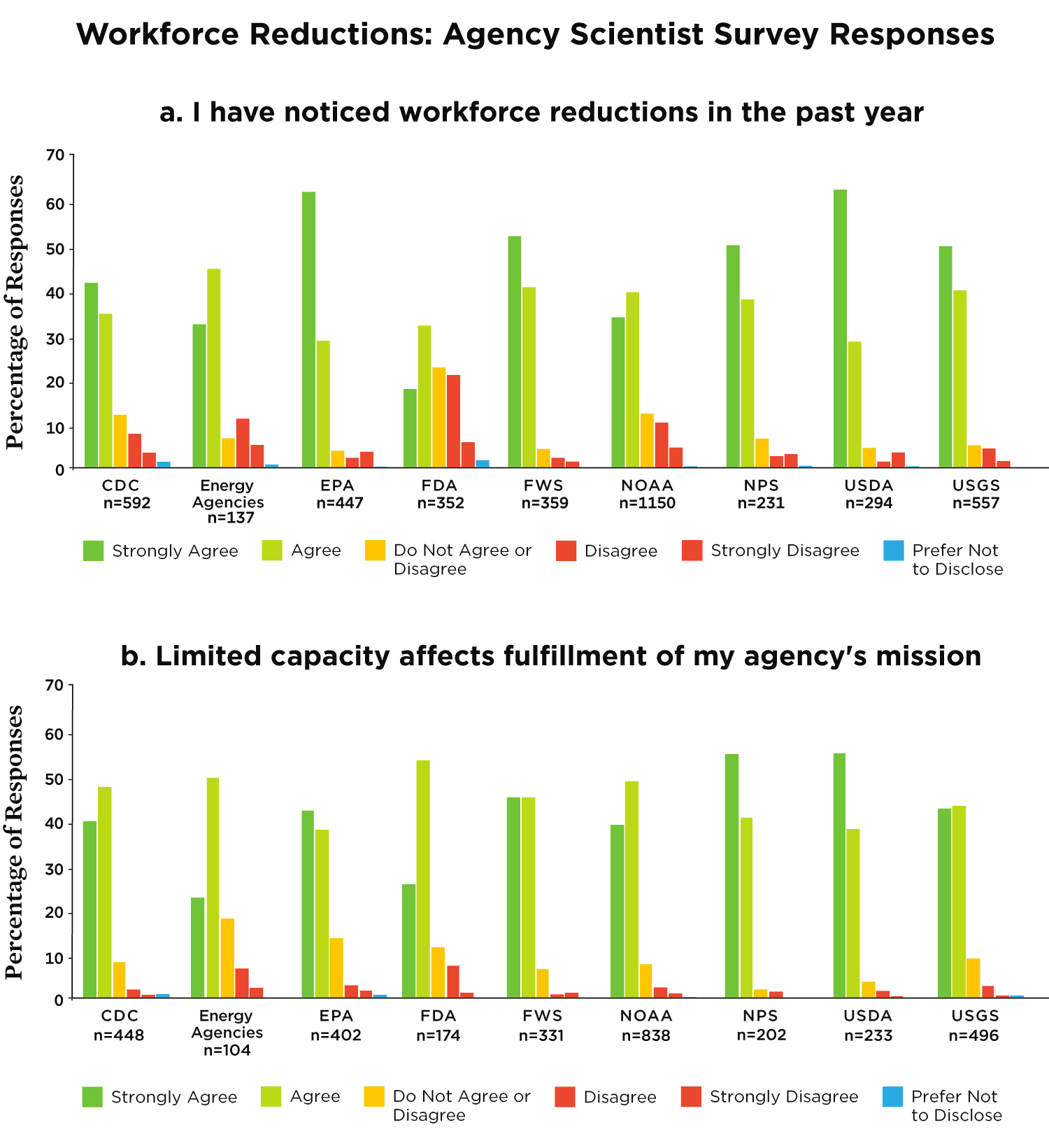

In our 2018 survey of federal scientists at 16 science-based agencies, 79 percent of respondents (3,266) reported workforce reductions in 2017 due to staff departures, retirements, or hiring freezes (Figure 6). Of the respondents who noticed workforce reductions, 87 percent (2,852) reported that such reductions made it more difficult for their agencies to fulfill their science-based missions.

The survey results also indicated that morale and job satisfaction were low for scientists under the Trump administration. Across all agencies, 39 percent of responding federal scientists (1,624) reported that the effectiveness of their divisions or offices had decreased in 2017, and 46 percent of scientists surveyed reported an overall decrease in job satisfaction during the same period.

Conclusion

Our data show that some agencies, such as the EPA, have seen significant losses in scientific capacity. These agencies make decisions that protect the health and safety of the public and the health of our environment—critical missions that will be difficult to fulfill if the agency lacks needed expertise. The Biden administration should work quickly, starting on day one, to restore scientific capacity to agencies that have lost scientists.

Moreover, merely restoring what was lost is not enough: The new administration should work to build and strengthen scientific capacity beyond pre-2017 levels. The administration also should work to diversify the scientific workforce at federal agencies and revitalize the pipeline that brings early career scientists into federal service.

We recommend that, in addition to taking steps to strengthen the role of federal science and scientific integrity across the government, the Biden administration:

- Increase the number of early career scientists entering the federal government by strengthening scientific fellowship programs.

- This could include, for example, reinstating the STEM-specific track of the Presidential Management Fellowship program.

- Early career fellowships already exist in some federal programs, (e.g., Sea Grant, Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education) and the Biden administration should consider funding similar fellowships that tackle other science-related issues such as climate change or equity and environmental justice.

- Increase public access to information and training on how to apply for federal positions on USAJobs.gov. Every effort should be made to provide such information to members of communities that have historically been underrepresented in federal scientific positions—for example, by hosting events at historically black colleges and universities and tribal colleges.

- Train mid-career and senior-level scientists to effectively mentor early career staff. Federal agencies should implement and increase such trainings if they already exist, and develop them if they do not.

- Signal strong support for increased scientific capacity in the White House science and technology budget, which sets the administration’s priorities for federal research and development.

These are some initial steps that the Biden administration may follow to begin strengthening the federal scientific workforce; however, rebuilding scientific capacity so that agencies can fulfill their important missions to protect public health and safety will take time. Therefore, the Biden administration should work hard to restore scientific experts to federal agencies on day one, focusing on agencies that have been hit hardest, such as the EPA. Bringing scientific expertise back to government will ensure that science can protect our environment, keep the public safe, and foster a healthier future for all.

Downloads

Citation

Carter, Jacob, Taryn MacKinney, Gretchen Goldman. 2021. The Federal Brain Drain: Impacts on Science Capacity, 2016-2020. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists. https://www.ucsusa.org/node/13931