Coal-fired power plant closures over the last decade have reduced air pollution and, as a result, improved public health. But there is another coal-era legacy that poses a serious health threat long after power plants are closed: the leftover ash residue from burning coal, which is teeming with arsenic, lead, radium, and other toxic elements.

Since the mid-1960s, US electric utilities have generated 4.5 billion tons of ash, and despite recent plant closures, they still produce an average of 100 million tons annually, which they mix in water and store in often leaky impoundments called coal ash ponds. There are more than 700 of these ponds across the country, and more than 20 percent of them are in the Ohio River Valley.

Plans that utilities have in place to clean up coal ash ponds do not go far enough, according to a report by the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Ohio River Valley Institute.

The report, which focuses on a site in southern Ohio and another in western Kentucky, recommends a "clean-closure" approach that would better protect public health and the environment and provide more local job opportunities than what either of the utilities plan to do.

The clean-closure proposal would cost more, but it would generate more jobs, address longtime environmental justice inequities, and produce more than $100 million in additional economic output in each state.

Repairing the Damage

This is a condensed, online version of the report. Access to all figures and full report are available through download of the PDF.

Although coal has powered the nation for generations and today offers well-paying jobs—often the best opportunities in more rural areas—coal negatively affects human health and the environment at every point in its life cycle: when it is mined, processed, transported, burned, and discarded. Local communities—often low-income communities and/or communities of color—have for decades borne the brunt of these negative impacts, including air pollution, water pollution, and workplace injuries, illnesses, and fatalities.

One of the Nation’s Largest Waste Streams

When coal is burned to produce electricity, not all of its components combust, leaving ash behind—massive amounts of it. Coal ash is one of the two largest industrial waste streams in the United States: From 1966 to 2017, US electric utility companies generated a total of 4.5 billion tons of coal ash and from 2015 to 2019 produced an average of 101 million tons of coal ash every year.

Coal ash is often mixed with water and stored in large impoundments, commonly called coal ash ponds. It can also be stored in dry form in landfills or reused in products like concrete. Many of the elements that make up coal ash—arsenic, boron, cadmium, chromium, lead, radium, and selenium, to name a few—are toxic, and exposure can cause a variety of severe health issues, including cancer, heart disease, reproductive failure, stroke, and even brain damage in children. Many coal ash constituents are also toxic to aquatic life, and disposal sites pose a risk of catastrophic spills that can contaminate soil, waterways, and groundwater. Despite being such a large waste stream with demonstrated serious impacts on human health and the environment, only in 2015 did the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) adopt monitoring standards and closure requirements for coal ash disposal sites under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

Coal Ash in the Ohio River Valley States

Coal-fired power plants are often located along major rivers because large amounts of water are needed for cooling, and many are concentrated along the Ohio River. Of the 738 coal ash disposal sites nationwide, 161 (more than one out of five) are found in the five states that make up the Ohio River Valley: Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. One assessment of documented groundwater contamination from coal ash disposal sites put two coal-fired power plants in the Ohio River Valley on the list of the top 10 most contaminated nationwide: the New Castle Generating Station in Pennsylvania (#5) and the Ghent Generating Station in Kentucky (#10).

These 161 disposal sites are located at 57 operating or retired coal-fired power plants in these five states. At 33 of the plants (58 percent), the surrounding community is considered low-income, meaning that the residents within a three-mile radius have an average income level at or below twice the federal poverty level in their state. Six of the 57 plants (nearly 11 percent) are located within three miles of a community with a disproportionate number of people of color; half are in Indiana. Nationally, 52 percent of communities near operating or retired coal-fired power plants are low-income—meaning that the Ohio River Valley disposal sites are more likely to affect low-income communities relative to the national average.

Case Studies Explore the Costs and Benefits of Complete Cleanup

Generalizing the costs of coal ash cleanup nationally is difficult because the cleanup needs are site-specific, but case studies are useful in understanding costs and needs under specific conditions and in providing context for the problem nationally. New analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Ohio River Valley Institute evaluates the cleanup costs and job creation potential for two coal ash sites—the first two such case studies in the Ohio River Valley. One, the J. M. Stuart coal-fired power plant in Appalachian Ohio, closed in 2018, along with another nearby coal plant, dealing a blow to the local economy. The other, the Sebree Generating Station, consists of three coal-fired power plants (one still in operation but slated for retirement) in western Kentucky. Our analysis evaluates site owners’ plans for cleanup activities (both of which are in violation of federal regulations) and proposes a more complete “clean closure” plan for both. These case studies illustrate how investing in cleanup of coal ash can create jobs in exactly the places where jobs are being lost as coal continues its decline. Clean closure simultaneously mitigates the harm caused by pollution begun in decades past and continuing to the present day by providing communities in the Appalachian region—and nationwide—a pathway forward as the shift toward clean energy continues.

Case Study Findings

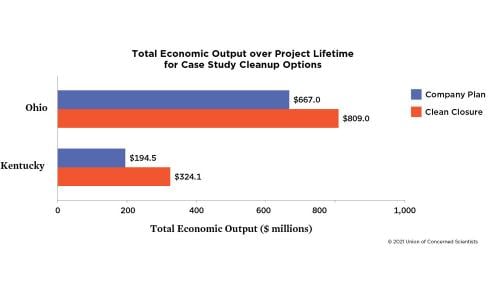

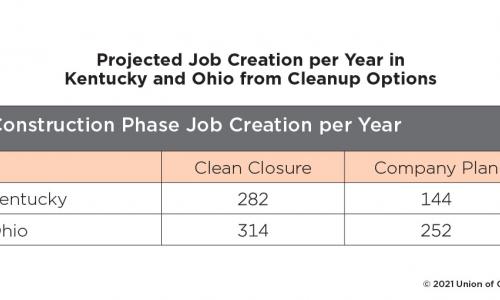

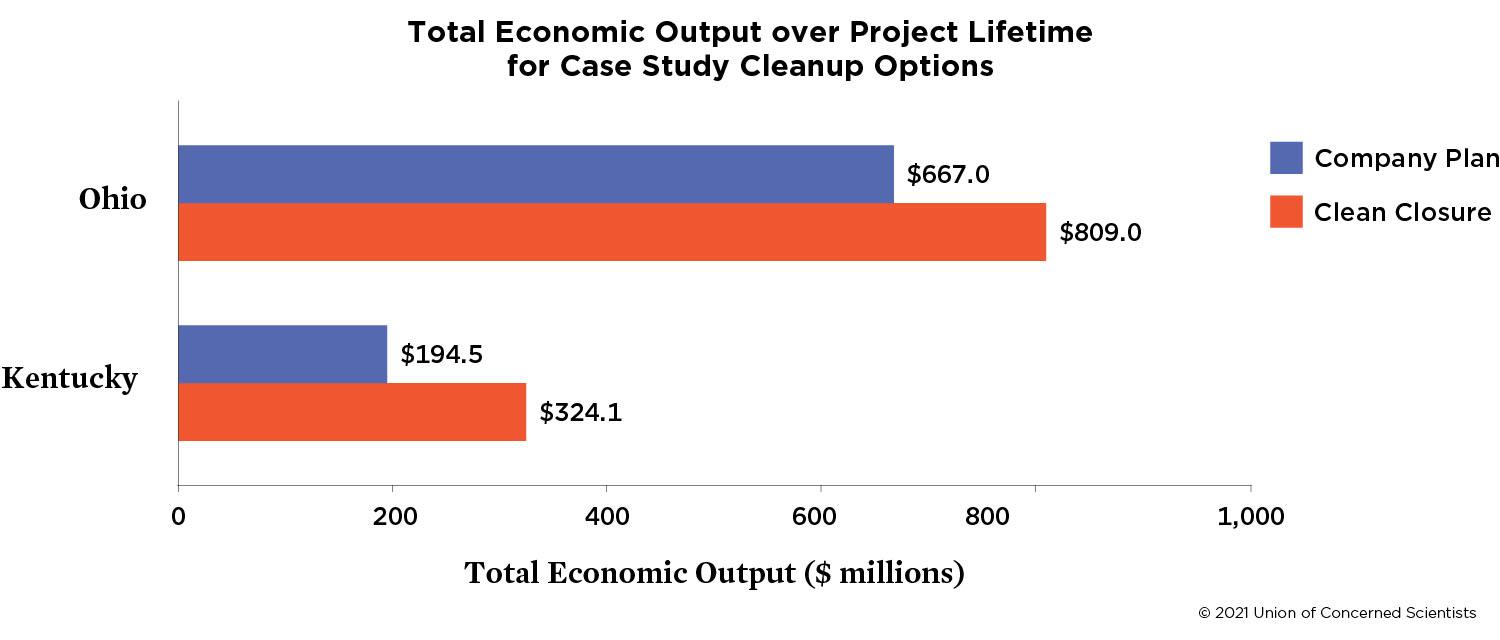

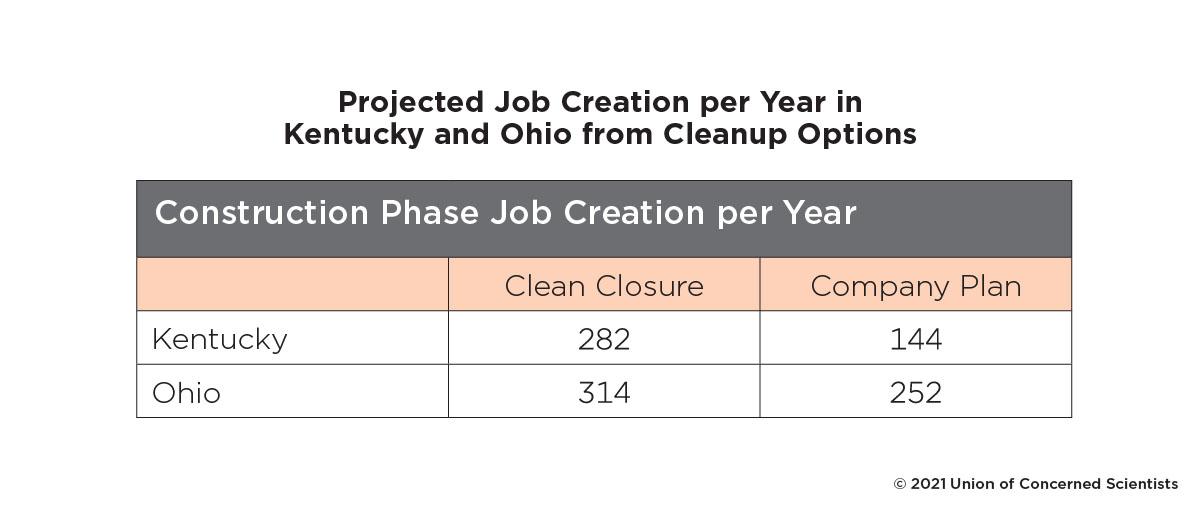

Our analysis consists of an engineering assessment of each site and a cost analysis of two cleanup options—the owner’s plan for closing the disposal sites and a proposed clean closure scenario that represents a complete set of actions to fully remediate the site, including excavation of coal ash ponds. Based on the cost estimates and direct job creation from the cleanup projects, we conducted an economic analysis of the impacts of the projects for each state’s economy. We found that the clean closure of coal ash disposal sites offers superior protection for public health and ecosystems while offering better opportunities for local jobs and associated economic activity, consistent with similar evaluations for other sites in previous reports. The additional costs of clean closure are justified by the higher number of jobs, the wider economic benefits, and the potential for redevelopment that flow to the local communities. This is especially true for the Sebree plant, where the clean closure plan would generate nearly twice as many jobs as the utility’s proposal during the project’s construction phase, which refers to initial investments in infrastructure needed to excavate and safely store the coal ash waste. As shown in Table 1, the clean closure options would lead to the creation of 282 jobs in Kentucky during the four-year construction phase and 314 jobs in Ohio during the nine-year construction phase. At both sites, the clean closure scenario would drive significant economic impacts that would ripple through each state’s economy, as shown in Figure 1. Relative to the owners’ cleanup plans, the clean closure plans drive more than $100 million in additional economic output in each state.

Recommendations

In addition to the job creation and local economic growth from cleaning up these two coal ash disposal sites, state and federal policymakers can take a number of actions to strengthen rules and increase funding to ensure that coal ash is cleaned up nationally.

-

Hold utilities and owners responsible for the clean closure of coal ash disposal sites. Cleanup decisions are governed by state regulators, and rate-regulated utilities typically petition state public utility commissions for cost recovery—meaning ratepayers are on the hook to pay for the cleanup. Regulators should consider the long-term economic value of cleanup options to the local community—ratepayers should not bear the costs without reaping the economic value of full cleanup.

-

Robustly fund existing EPA programs that support communities. EPA programs must be robustly funded to ensure that polluting coal ash disposal sites are identified and cleaned up. These programs include the Brownfields programs, enforcement divisions, and the Corrective Action Program within the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

-

Strengthen the enforcement of existing regulations that prohibit cap-in-place closure. The EPA already has enforcement authority, and it can and should follow the plain language of the 2015 Coal Combustion Residuals Rule, requiring excavation when coal ash is in contact with groundwater or when coal ash ponds would remain in a floodplain when capped in place. States should also require excavation under state laws and regulations, as is being done in North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and Illinois.

-

Ensure that frontline communities have a voice in cleanup decisions. Residents and community leaders are often the strongest voices in holding utilities and site owners accountable for cleanup, and robust stakeholder processes are needed to ensure meaningful engagement. For example, the EPA’s Technical Assistance Services for Communities Program offers grants that can empower fenceline communities and residents to participate in discussions about closure options. It is a valuable resource that should be robustly funded to drive better local outcomes, and additional programs supporting environmental justice communities may also be brought to bear.

-

Ensure strong labor standards and safety protections for cleanup workers and prioritize dislocated workers in hiring. Local hiring requirements should be implemented to ensure that dislocated workers have access to cleanup jobs, and prevailing wages should be required to ensure that workers are paid fairly for their work. Because coal ash is toxic, workers must be protected during cleanup activities.

-

Prevent damage to communities and the environment from reuse of coal ash. The EPA should cease classifying unencapsulated coal ash as an acceptable “beneficial use” and instead treat unencapsulated uses as a form of disposal.

-

Ensure that the extraction of rare earth elements is safe and is coupled with clean disposal of remaining coal ash. A holistic assessment of risks and benefits should be applied to rare earth element extraction, and extraction programs should be informed by the community and unions.

-

Leverage existing federal programs or consider establishing new financial institutions or grant programs to ensure that all disposal sites nationally are fully cleaned up. Existing federal programs like the Superfund program could be augmented through polluter-pays fees. Additional public financing may be needed to ensure complete removal of coal ash. These resources are critical for ensuring a fair transition to clean energy for communities and workers formerly dependent on coal-fired electricity production.

Jeremy Richardson is a senior energy analyst in the UCS Climate and Energy Program. Eric Dixon is an independent consultant working with the Ohio RIver Valley Institute. Ted Boettner is a senior researcher at the Ohio Valley Research Institute.

This is a condensed, online version of the report. Access to all figures and full report are available through download of the PDF.

Downloads

Citation

Richardson, Jeremy, Ted Boettner, and Eric Dixon. 2021. Repairing the Damage: Cleaning Up Hazardous Coal Ash Can Create Jobs and Improve the Environment. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists and Ohio River Valley Institute.