Gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles 20 years old or older expose Californians to significant harmful air pollution even though they represent a relatively small fraction of the passenger vehicles on the road.

Moreover, the harm falls disproportionately on Latino and Black Californians, lower-income households, and communities the state designates as disadvantaged. To ensure that all Californians have access to cleaner transportation options, the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Greenlining Institute recommend the following changes in state policies and programs:

- Prioritize existing incentive programs, such as Clean Cars 4 All and the Clean Vehicle Assistance Program, toward priority populations owning old cars.

- Target outreach and education to households in areas with high concentrations of old cars and limited uptake of zero-emissions vehicles.

- Provide transportation solutions that go beyond private passenger vehicles.

- Evaluate and adjust incentive programs based on changing conditions in the electric vehicle market.

Cleaner Cars, Cleaner Air

This is a condensed, online version of the report. For all figures, references, and the full text, please download the full report PDF.

California has a long history of poor air quality resulting from transportation pollution on its roads. As early as 1966, the state's climate, geography, and large number of vehicles led California to initiate regulatory action to reduce pollution from passenger cars and trucks. As a result of continuing progress on regulations, the air-polluting emissions of new passenger vehicles currently for sale are much lower than those of older vehicles.

Gasoline vehicles result in emissions that both directly and indirectly produce fine particulate matter, defined as airborne particles less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter. Referred to as PM2.5, these particles are small enough to penetrate deeply into the lungs; some can even enter the bloodstream. Chronic exposure to PM2.5 causes increased death rates attributed to cardiovascular diseases, including heart attacks, and it has been linked to lung cancer and other adverse impacts. Chronic exposure in pregnancy and childhood has also been linked to slowed lung-function growth and the development of asthma, among other negative health impacts.

A Fraction of the Vehicles on California Roads, Older Cars and Trucks Pollute More Than Newer Ones

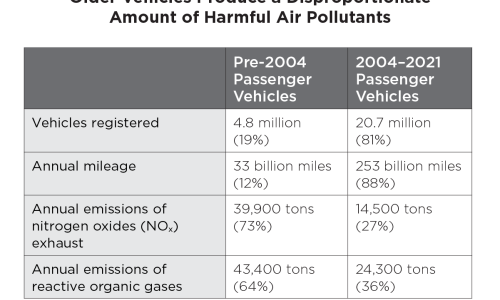

Beginning with model year 2004, California implemented updated Low-Emission Vehicle (LEVII) tailpipe pollution standards for passenger vehicles that required significant reductions in air pollution emissions. Older vehicles (pre-2004) make up 19 percent of the state's passenger vehicles and only 12 percent of miles driven, yet they emit almost three times as much smog-forming nitrogen oxides pollution as all 2004 and later vehicles combined. They are responsible for 73 percent of all nitrogen oxides exhaust from passenger vehicles and 64 percent of reactive organic gases (Table 1). These pollutants can react in the atmosphere to form harmful PM2.5 pollution.

Although older vehicles represent fewer than one-fifth of the cars on California roads, they produce more nitrogen oxides and reactive organics gas emissions than all newer vehicles combined.

Exposure to Harmful Air Pollution from Older Vehicles Is Inequitably Distributed

Using the InMAP air-quality model and data from the California Air Resources Board, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) and The Greenlining Institute (Greenlining) estimated the formation and transport of PM2.5 pollution from the use of older passenger vehicles (defined as model year 1976 through 2003) and newer ones (model year 2004 through 2021).1 Combining the PM2.5 pollutant concentration with US Census data, we estimated the exposure of Californians to harmful air pollution from older cars.

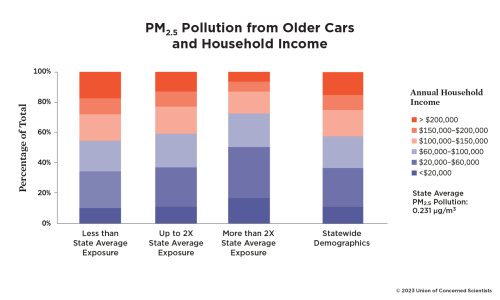

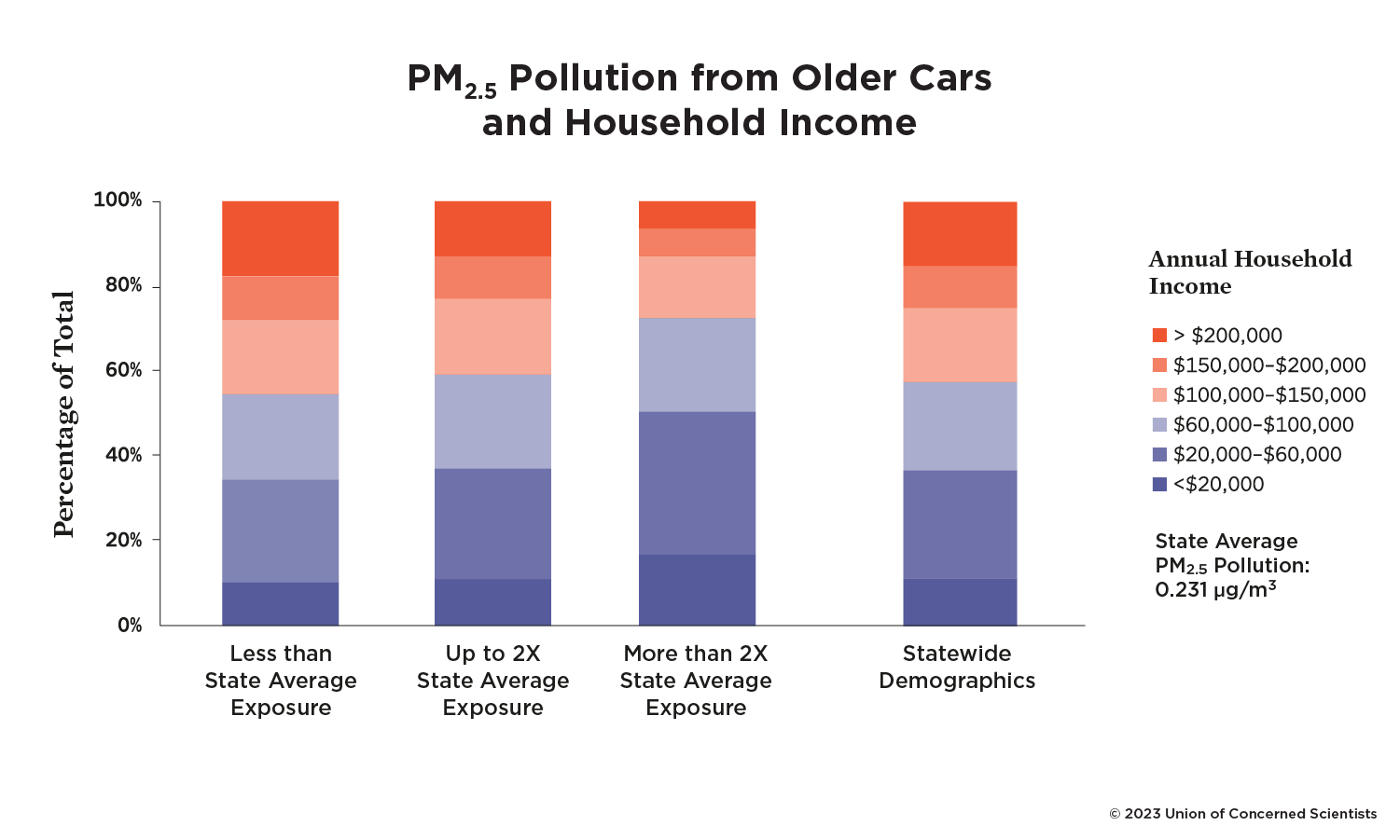

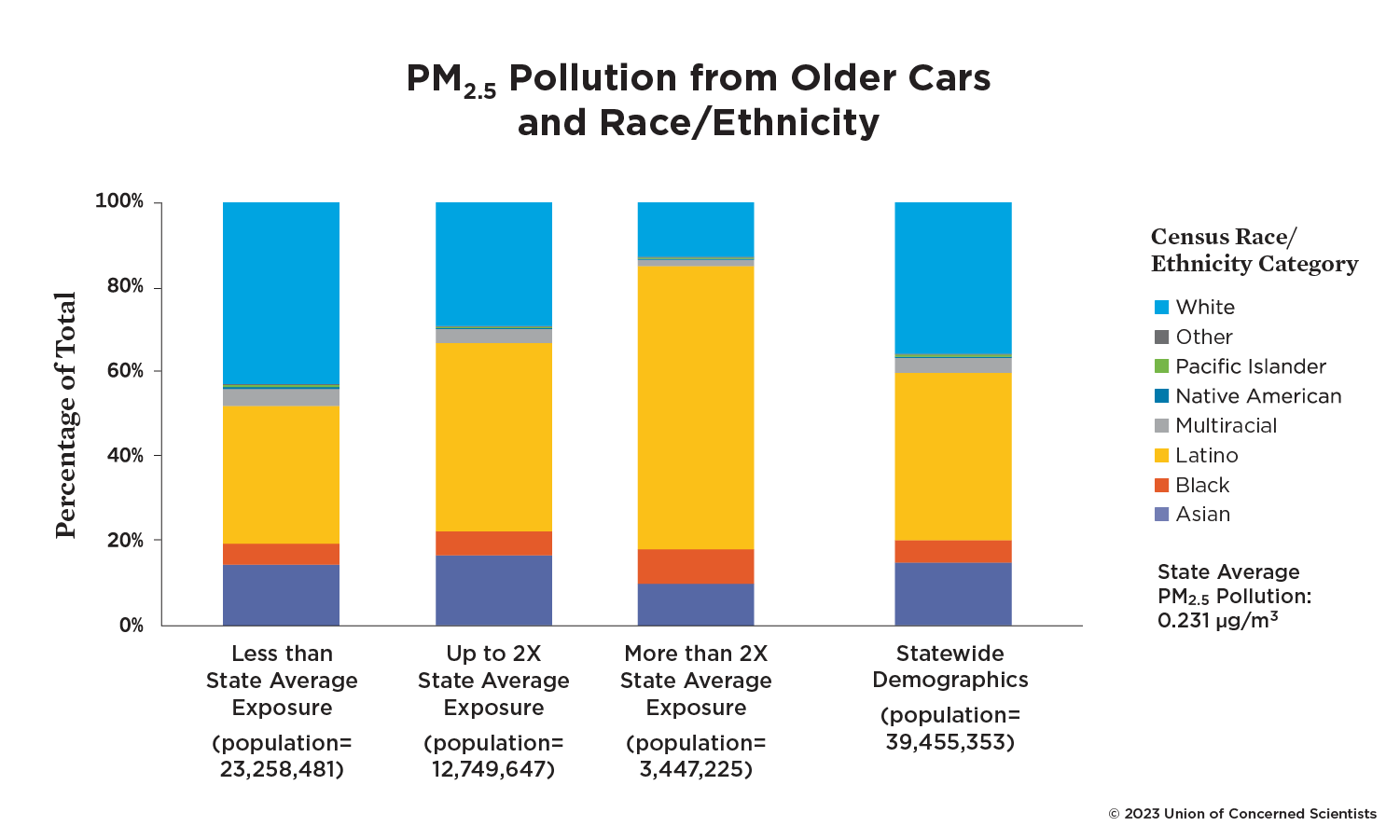

Our analysis shows that PM2.5 exposure from the use of pre-2004 vehicles is inequitably distributed across racial and demographic groups in California. All of the areas with the highest exposure to PM2.5 from older vehicles are in the southern half of California and mainly in central Los Angeles. The communities with the highest pollution burden due to PM2.5 from older vehicles---more than twice the state average---have a higher percentage of low- and moderate-income households than areas unburdened by air pollution from these vehicles.

In the parts of the state with the highest exposure to PM 2.5 pollution from older vehicles, over half of households have an income of less than $60,000 a year. In areas with the least exposure, only 35 percent of households have an income of less than $60,000 a year (Figure 1). On average, higher-income households are exposed to lower concentrations of PM2.5 pollution from all passenger vehicles. Higher-income households also experience significantly less exposure to pollution from older vehicles.

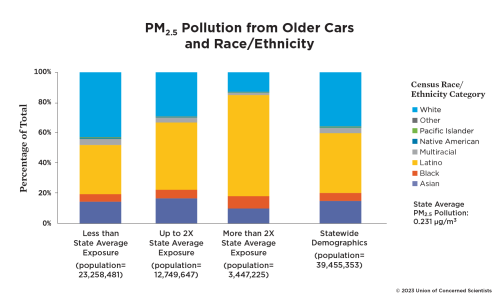

We also found racial and ethnic disparities in the exposure to air pollution from passenger vehicles. These disparities, too, are greater for pollution from older vehicles than for the fleet as a whole. For all passenger cars and trucks, White people are exposed to 17 percent lower concentrations of PM2.5 than the state average, while Latino Californians are exposed to 13 percent higher concentrations and Black Californians are exposed to 11 percent higher concentrations.2

Looking only at pollution from older vehicles, White Californians are on average exposed to 20 percent lower concentrations of PM 2.5 than the state average. Latino Californians are exposed to 19 percent higher concentrations, and Black Californians are exposed to 12 percent higher concentrations.

Communities with the highest exposure to PM2.5 from older vehicles---greater than twice the state average---are home to much higher proportions of Black and Latino people than the state as a whole. In these areas with the highest exposure, 67 percent of residents are Latino and 8 percent are Black; the state as a whole is 40 percent Latino and 5 percent Black. In contrast, those same areas of highest exposure are only 13 percent White; the state is 36 percent White (Figure 2).

Further, Californians who already face the worst exposure to pollution from all sources also face the brunt of emissions from older vehicles. Increased exposure to PM 2.5 pollution from older vehicles correlates with a community's score on CalEnviroScreen 4.0, a screening methodology that helps identify communities that are disproportionately burdened by multiple sources of pollution. People in the highest-scoring (most-burdened) census tracts in CalEnviroScreen 4.0 are exposed to twice the concentration of pollution from older vehicles as are those in the lowest-scoring census tracts.

Estimating Premature Deaths Due to Pollution from Older Vehicles

To estimate the health impacts of PM2.5 pollution exposure resulting from older vehicles, we examined two scenarios considering the emissions from engine starts, evaporative emissions, and driving. These scenarios provided a range for the estimated premature deaths in California. One scenario only considered cold-start emissions and assumed those happen where the vehicle is registered. The second scenario assumed that all tailpipe emissions happen where the vehicle is registered. We estimated that older-vehicle emissions led to between 97 and 421 premature deaths per year. The impacts were concentrated in Southern California, especially Los Angeles County.

Rural Areas Have a Higher Proportion Of Older Vehicles

While Southern California's urban areas have the most older vehicles (and highest exposure to the resulting pollution), rural areas have higher proportions of older vehicles. For example, in rural Modoc, Trinity, and Sierra counties, over 40 percent of vehicles are model year 2003 or older. In contrast, Orange, San Francisco, and Riverside counties, all of which are much more urban, have the lowest percentages of older cars in the state.3

Recommendations: Policies to Reduce Inequitable Exposure to Pollution

Based on the impacts of older cars on local air quality and public health, it is imperative that California agencies administering incentive programs for retiring and replacing vehicles prioritize getting the oldest cars off the state's roads. Policymakers should also ensure that programs provide direct, measurable and meaningful benefits to disadvantaged and low-income communities. Moreover, when developing new policies and programs, California should involve---and in meaningful ways---the communities most impacted by older-vehicle emissions. This will help the state identify approaches to reducing the inequitable distribution of this pollution from older passenger vehicles.

UCS and Greenlining recommend the following changes in state policies and programs:

-

Prioritize incentives toward priority populations owning old cars. State agencies should integrate programmatic changes to existing incentive programs, such as Clean Cars 4 All and the Clean Vehicle Assistance Program, to prioritize investments in low-income and disadvantaged communities with high concentrations of older cars.

-

Engage in intentional, targeted outreach and education to areas with high concentrations of old cars. State and local agencies should target their limited outreach and education funds to households in areas with high concentrations of old cars and limited uptake of zero-emissions vehicles.

-

Provide transportation solutions that go beyond private passenger vehicles. Even as California attempts to reduce vehicle miles traveled, it continues to invest in vehicle incentive programs that prioritize car ownership. Agencies should consider further funds for programs that promote alternative modes of transportation, such as public transportation, walking, car sharing, and (e-)biking.

-

Evaluate and adjust incentive programs based on changing conditions in the electric vehicle (EV) market. Despite declining prices for EVs, the pandemic's impact on the supply of EVs has created barriers to the purchase of both new and used EVs. California should continue to evaluate and adapt its incentive programs to best assist people based on their needs. While a complete switch to zero-emissions technology will happen in the longer term, the prices and limited supply of electric vehicles can make their purchases more difficult in the near term. Thus, the state should not discourage drivers from switching to other types of cleaner and cheaper-to-fuel vehicles, even those that are not zero emissions.

Conclusion

A cleaner, safer transportation future for all Californians is possible. To realize it, the state must commit to retiring the dirtiest vehicles on the road. With sustained investment and targeted policies, California can protect its vulnerable communities from harmful air pollution, saving money and lives.

Endnotes

1We excluded vehicles older than 1976; our input sources lacked detailed data on vehicles manufactured before 1976. The newest vehicles in the dataset were model year 2021.

2 This report uses the term Latino to describe persons answering "yes" to the US Census question "Is this person of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?" The census collected race data in a separate question. The term White describes persons answering "no" to the Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish ethnicity question and choosing the response "White" in response to "What is this person's race?" The term Black describes persons answering "no" to the Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish question and choosing "Black or African Am." in response to "What is this person's race?"

3 Maps showing pollution concentration and vehicle distribution are available online at https://blog.ucsusa.org/dave-reichmuth/cleaner-cars-cleaner-air.

This is a condensed, online version of the report. For all figures, references, and the full text, please download the full report PDF.

Downloads

Citation

Beyer, Matthew, Ashley Gerrity, Román Partida-López, and David Reichmuth. 2023. Cleaner Cars, Cleaner Air: Replacing California's Oldest and Dirtiest Cars Will Save Money and Lives. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/cleaner-cars-cleaner-air.