Each morning, many millions of Americans start their day with a bowl full of corn, wheat, oats, or other grains. According to a 2018 survey, nearly 90% of us eat cereal for breakfast at least once in a while. That’s a lot of grain—and it gives cereal makers a lot of leverage to help farmers change our agricultural system for the better. Our 2019 report, Champions of Breakfast, crunches some numbers to show what that change could look like, and offers specific recommendations for getting us there.

The impact of current grain production practices

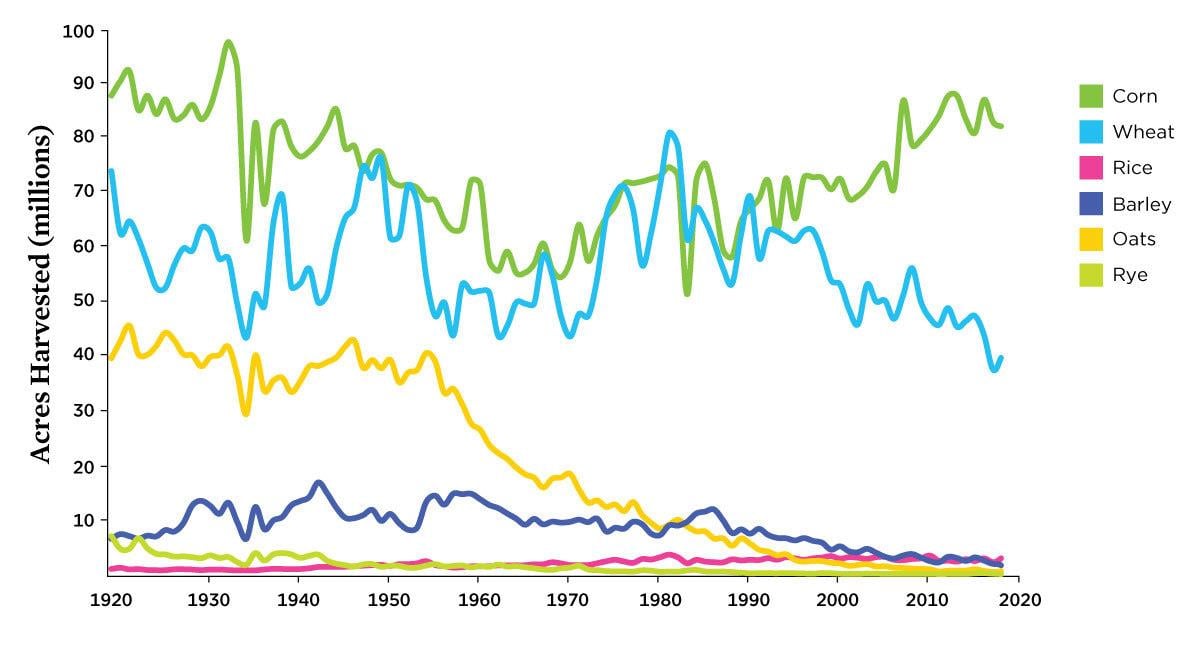

In recent decades, US agriculture has become dominated by a few major crops. In 2017, corn and wheat covered areas about the size of New Mexico and Washington state respectively, while other grains, such as oats, have all but disappeared from the landscape.

These few dominant cereal grain crops are commonly grown continuously on the same land, or rotated with just one other crop, and crop fields are often plowed and left bare between growing seasons. These practices leave farmland susceptible to erosion and reduce its sponge-like capacity to absorb and hold water—a recipe for downstream pollution as runoff from heavy rainfall and floods washes soil, fertilizers, and pesticides into nearby waterways. These pollutants contaminate drinking water, threaten public health, clog shipping channels, and damage fisheries and ecosystems.

Farming in ways that protect soil and water

Putting grains on our breakfast tables doesn’t have to do all this damage. Some farmers are forging a different path, successfully employing a variety of practices that science has shown can reverse soil damage, improve water quality, and help farmers adapt to and mitigate climate change:

- Cover crops can be planted when main crops aren’t growing. They prevent erosion, soak up nutrient-rich water before it escapes to surrounding waterways, and help build soil health. Cover crops that are legumes have the added benefit of enriching soils with nitrogen from the atmosphere; this can lessen the need for nitrogen fertilizers for subsequent crops, reducing pollution as well as farmers’ costs.

- Conservation tillage, which means little or no plowing of the soil, keeps soil protected and organic matter in the ground, reducing or reversing erosion and soil carbon losses.

- Soil-building crop rotations, which involve three or more crops in succession, can interrupt pest cycles and reduce the need for pesticides as well as helping build soil health.

- Perennial plants—including alfalfa, prairie grasses, and even shrubs and trees—can be incorporated into farms, where their deep roots can help build healthy, spongy soils and prevent water pollution.

Research shows that healthy-soil practices like these can be combined and scaled up to deliver substantial benefits for combatting floods, drought, water pollution, and erosion. But many farmers face up-front costs and market obstacles to adopting these practices.

The role cereal makers can play

So, what does all this have to do with my cornflakes?

While the breakfast food industry is a relatively minor user of US grains, cereal is a beloved and highly visible lever for improving the sustainability of our food and farm system. Four companies account for 86 percent of the $8.5 billion US breakfast cereal market; many of their brands are household names, and they make more than just cereal. By investing in supply chain improvements, defining and improving sustainability standards, and raising consumer awareness, these companies can help expand opportunities for sustainable grain farmers, setting the wheels in motion for larger-scale market shifts.

And recently, some of these companies have begun to step up. For instance, General Mills has pledged to shift 1 million farm acres to regenerative agriculture practices by 2030. Other companies, including PepsiCo (the parent company of Quaker Oats) and Kellogg Company, are also participating in sustainable-grains initiatives. These initial commitments are promising—and they need to be implemented and expanded rapidly to drive real changes at the needed scales.

What our study found

In our analysis, we estimated the environmental benefits for three grain purchasing scenarios. In each, a company uses more sustainable sourcing standards to purchase a specified amount and type of grain:

Scenario 1 is based on the amount of corn used annually in Kellogg's Frosted Flakes (2017’s top-selling corn cereal). This could shift 10,000 to 30,000 acres to a more sustainable cropping system.

Scenario 2 is based on the amount of oats used annually in General Mills' Honey Nut Cheerios (2017’s top-selling oat cereal). This could shift 60,000 to 180,000 acres.

Scenario 3 involves the amount of oats needed to produce an equivalent number of servings of whole-grain oatmeal as compared with the grains required to produce a top-selling ready-to-eat cereal brand. This could shift 140,000 to 420,000 acres.

The potential benefits we found include:

- Reduced erosion, ranging from up to 12,150 metric tons in Scenario 1 to up to 170,100 metric tons in Scenario 3—with cleanup cost savings ranging from $69,000 to nearly $1 million.

- Reduced heat-trapping emissions from nitrogen fertilizer. This could range from the equivalent of taking about 840 cars off the road in Scenario 1 to 11,760 cars in Scenario 3.

- Reduced fertilizer runoff, with cost savings from prevented freshwater nitrogen pollution alone ranging from around $827,000 to nearly $12 million. It's important to remember that these numbers involve shifting grain sourcing for a few individual brands, not for these companies' entire product lines. If such changes could be implemented on a larger scale, the environmental, economic, and climate benefits could be enormous.

It's important to remember that these numbers involve shifting grain sourcing for a few individual brands, not for these companies' entire product lines. If such changes could be implemented on a larger scale, the environmental, economic, and climate benefits could be enormous.

Recommendations

What can be done to drive these beneficial changes forward? Companies and policymakers both have important roles to play. Here are some recommendations from the report (for details, see the report document):

- Cereal-makers and other major grain producers should establish strong purchasing commitments to advance healthy-soil farming practices (or expand existing commitments) and implement such commitments swiftly.

- Food companies should advocate for state and federal healthy-soil policies that accelerate or incentivize the production of sustainably grown grains as a complement to their own purchasing commitments.

- Policymakers in every state should introduce and implement policies that support farmers in adopting healthy-soil practices.

- Congress and the US Department of Agriculture should do more to drive farmers' transition to healthy-soil practices: strengthening existing programs, creating new ones, increasing the availability of technical assistance through university-based extension programs, investing more in public research programs and public-private partnerships, and advancing infrastructure for new crop rotations and profitable markets for oats and other added crops.

Downloads

Citation

DeLong, Marcia, Karen Perry Stillerman. 2019. Champions of Breakfast: How cereal makers can help save our soil, support farmers, and take a bite out of climate change. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/champions-breakfast