A year and a half into the Trump administration, its record on science policy is abysmal: undermining the role of science in decision-making, expanding the influence of regulated industries, excluding public voices, censoring scientists, overriding and dismissing science advice, and hindering the collection and dissemination of scientific information. UCS has documented this poor record in our 2017 report, Sidelining Science from Day One, on our blog, and in our ongoing "Attacks on Science" web feature.

But what do scientists themselves think? What does the Trump administration's assault on federal science look like to the people who experience it every day in their workplaces?

We decided to ask. In February and March 2018, in partnership with the Center for Survey Statistics and Methodology at Iowa State University, we surveyed thousands of scientific experts employed by the federal government. Responses from more than 4,200 federal scientists are compiled in our report, Science Under Trump: Voices of Scientists across 16 Federal Agencies, in which scientists share openly and anonymously what they are experiencing.

The results should be disturbing to anyone who believes that government science has a crucial role to play in making the United States a safer, healthier nation. Federal scientists describe a broad range of problems, including workforce cuts, censorship and self-censorship, political interference, and undue industry influence. Unsurprisingly, these problems have taken a toll on morale, making it hard for scientists to do their jobs effectively.

The severity of reported problems varied widely across agencies, with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of Interior (DOI) faring poorly and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) doing relatively well.

Workforce reductions

Reduced funding for particular activities has led to reduced programs, job uncertainty, staff turnover, hiring freezes. These factors have delayed program implementation or led to their cancellation.

Scientific experts in the federal government are essential to ensuring that policies are grounded in the best available science. Yet the Trump administration has presided over an unprecedented hollowing out of the federal science capacity. Eighteen months into his administration, President Trump had filled just 25 of 83 posts designated by the National Academy of Sciences as "scientist appointees"—far fewer than in previous administrations. And science-based federal agencies are losing expertise as scientists leave government service through early retirements, hiring freezes, and other workforce reduction measures. Staffing at the EPA, for example, is at its lowest level in 20 years—and the Trump budget calls for a further reduction.

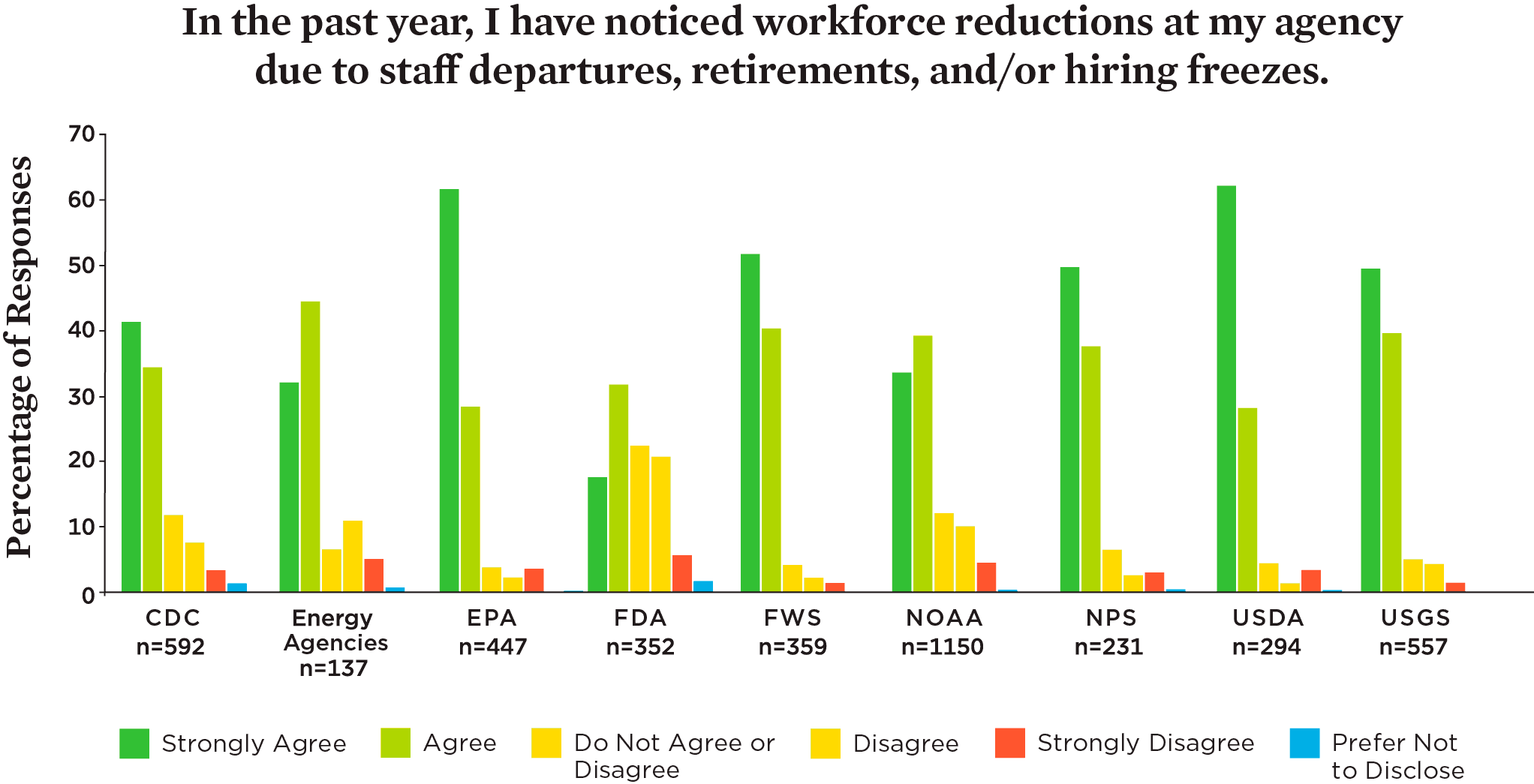

Survey results show that scientists are concerned about these staffing cuts. 79 percent of respondents reported workforce reductions during the past year, and 87 percent of this group reported that the reductions made it more difficult for agencies to fulfill their missions.

Political interference

We all just want to do our jobs to the best of our abilities, using the best evidence-based methods. But even those who have spent 30+ years at CDC are concerned that, for the first time, politics are being put above science.

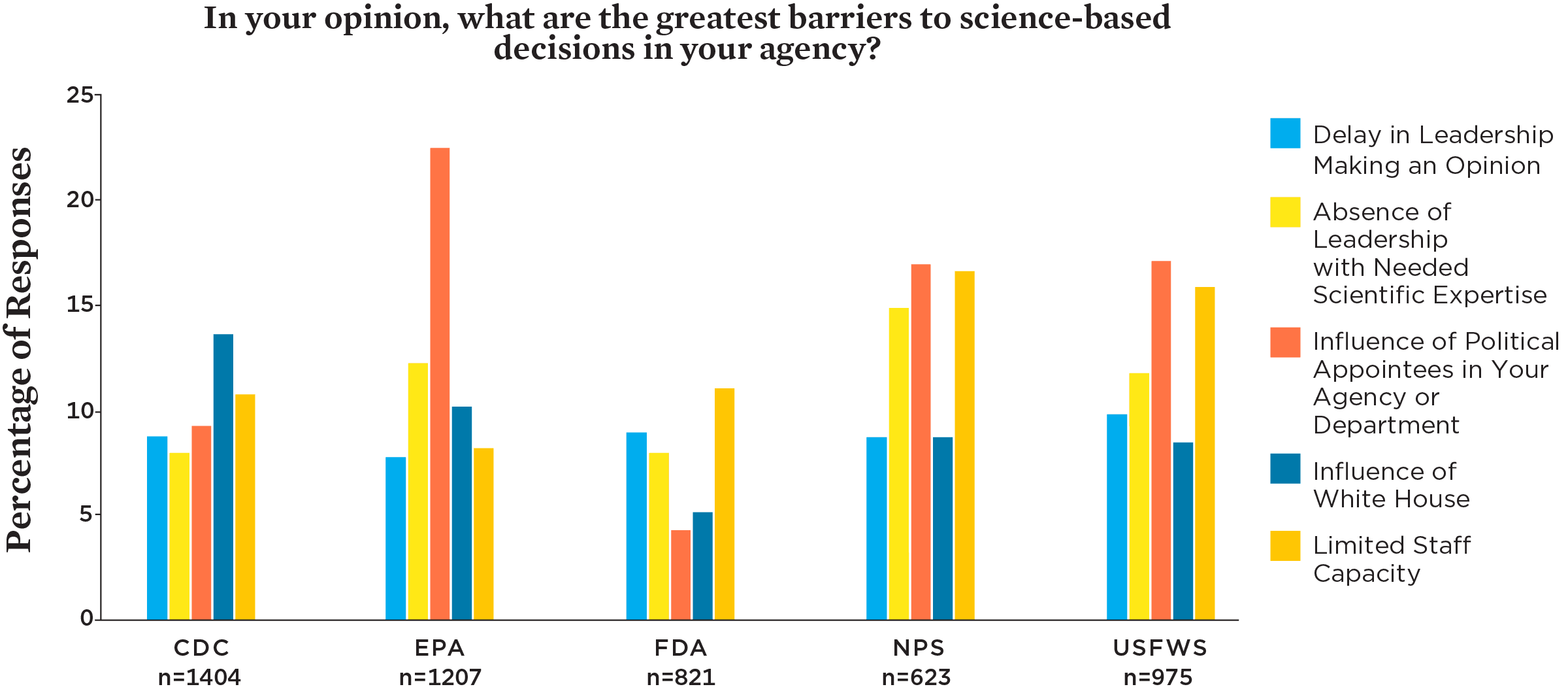

Scientists surveyed widely agree that the influence of political appointees within their agencies and by the White House presents a major barrier to science-based decision-making. UCS and others have identified many examples of such interference over the first 18 months of the Trump administration, such as the delayed publication of a study measuring the health effects of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Survey results show that 20 percent of all respondents named either "influence of political appointees in your agency or department" or "influence of the White House" as one of the greatest barriers to science-based decisionmaking. 50 percent of all respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that consideration of political interests hindered their agencies' ability to make science-based decisions. Respondents from the EPA showed particular concern about political influence, with 81 percent agreeing or strongly agreeing that it was a hindrance, and nearly a third naming it as a top barrier, to science-based decisions.

Censorship

We are no longer authorized to share scientific findings with the public if they center on climate change. Materials are marked as only for internal use.

Censorship has been a problem in the Trump administration from the beginning, as the White House and various agencies have removed mentions of climate change from websites and instructed staff to avoid referring to climate change in their communications. Survey results suggest that such censorship has been especially acute for National Park Service (NPS) scientists, much of whose work is hard to describe without mentioning climate change and its impacts.

The problem often manifests as self-censorship: scientists who know that climate change is now an unwelcome topic may elect to avoid the issue even before being told to do so.

Survey results show that 18 percent of respondents (including 47 percent at NPS and 35 percent at EPA) had been asked to omit the phrase "climate change" from their work. And 20 percent of respondents reported engaging in self-censorship regarding climate change.

Low morale

The constant attacks on science and facts by the current administration has negatively impacted scientists in the agency. Effects range from anger and frustration to depression and even opting to retire early. Twenty-five years of experience with 3 federal agencies and I’ve never seen anything like this—it is appalling.

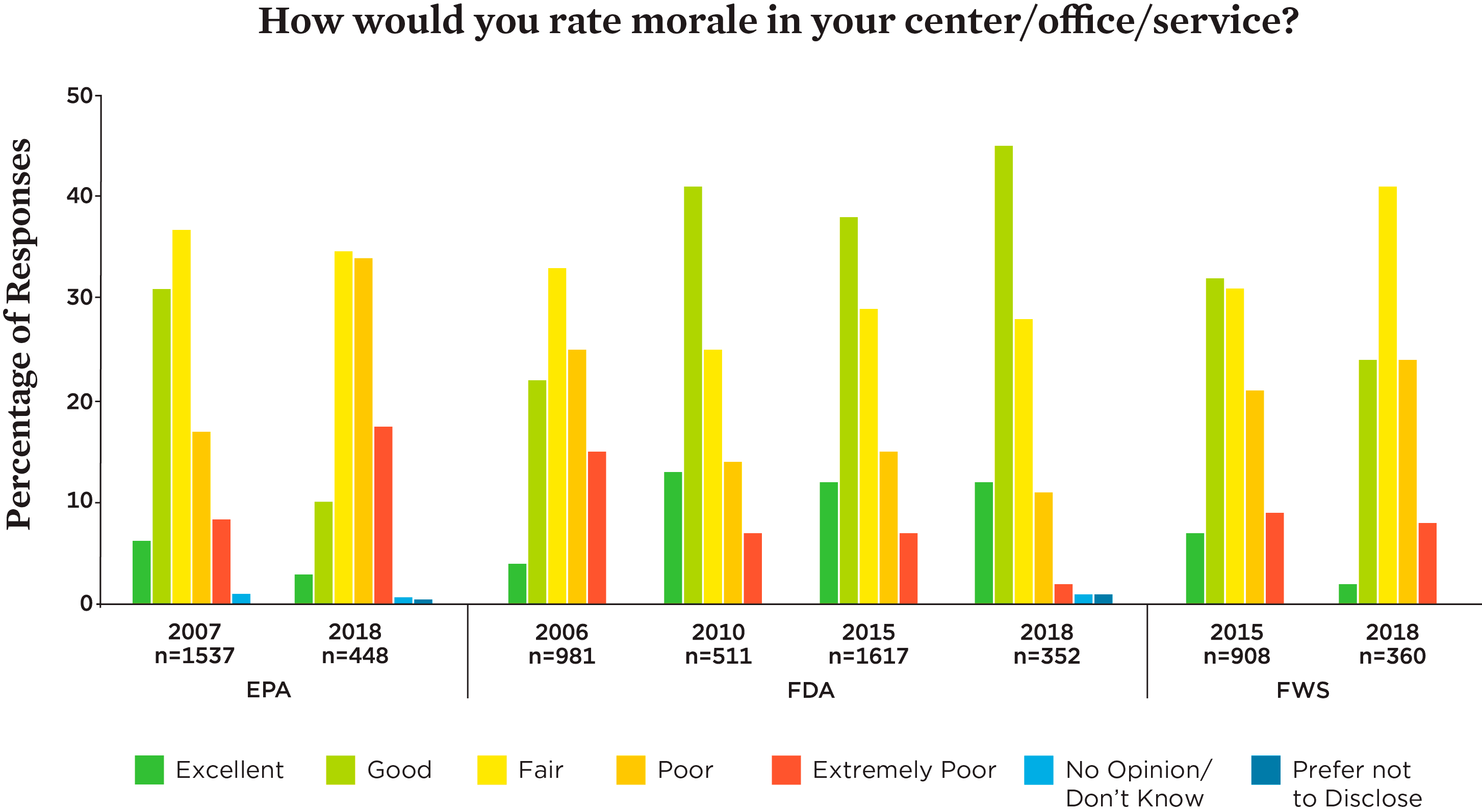

It's hardly surprising, given the kinds of problems our respondents described, that many scientists reported low morale at their agencies. There was considerable variation among agencies in this area: a majority of FDA scientists, for instance, reported morale as excellent or good, compared to less than 15 percent of EPA scientists. Reports of poor morale were strongly associated with perceptions of poor leadership.

Many respondents reported decreased job effectiveness and satisfaction in addition to low morale. Across all agencies, 39 percent of responding scientists reported that the effectiveness of their divisions or office had decreased over the past year, while only 15 percent reported an increase. Again, the largest percentage of respondents reporting described job effectiveness and satisfaction were at the EPA.

Scientific integrity policies

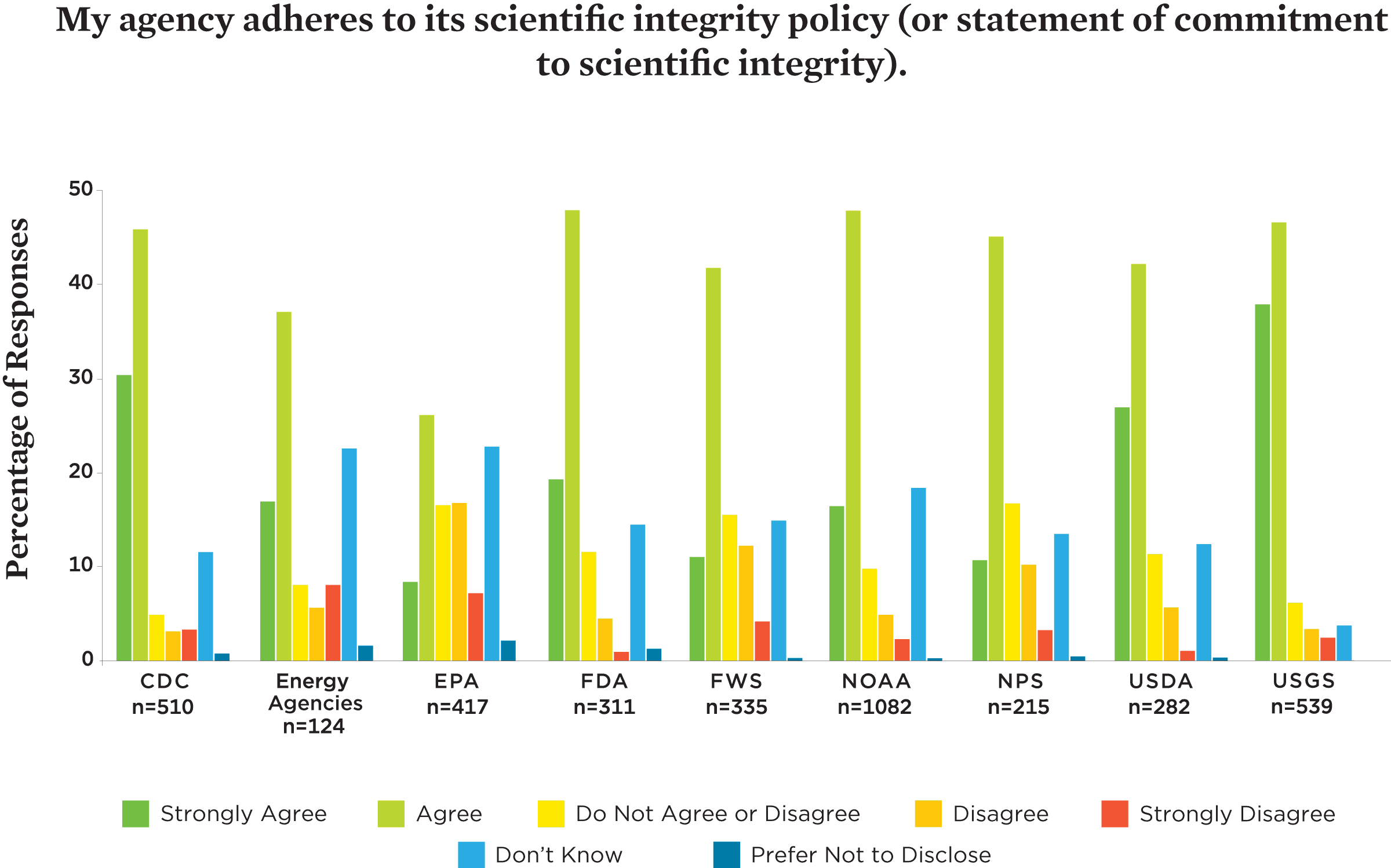

One of the few bright spots that emerged from the survey concerned agency scientific integrity policies. At least 28 federal agencies have such policies. Majorities of respondents agreed that their agencies adhere to their scientific integrity policies (64 percent) and that they had been adequately trained on both those policies (60 percent) and their whistleblower rights and protections (68 percent). Only 42 percent, however, said that they would be willing to report a scientific integrity violation and trust that they would be treated fairly.

Recommendations

When government scientists cannot do their jobs effectively, the public suffers. The Trump Administration has done much damage to the federal scientific enterprise in its first eighteen months. The report offers several recommendations for actions agency leaders can take to undo this damage:

- show respect for the value of independent science and publicly support agency science;

- act to reduce inappropriate industry influence on agency scientific work and science-based policy decisions;

- foster an environment conducive to effective work for agency scientists;

- stop censoring results or terminology that are legitimate products of the scientific process;

- encourage scientists to speak freely to the public and the news media about their work;

- remove barriers to the timely public dissemination of scientific information;

- provide appropriate resources and time for federal scientists to participate in professional meetings and other professional development opportunities;

- continue to facilitate training on scientific integrity policies and whistleblower rights.