Healthy communities require healthy democracy. When communities are disenfranchised or underrepresented, it becomes harder for them to use democratic institutions effectively to solve their problems and advocate for their interests.

This is the predicament faced by many environmental justice (EJ) communities—communities of color and low-income communities exposed to disproportionately high levels of toxic pollution and other environmental burdens. A 2018 analysis by the Center for Science and Democracy shows how restrictive election laws, gerrymandering, and other factors combine to further reduce already low voter turnout in these communities, weakening their ability to protect themselves against environmental hazards.

Mapping the voting/EJ connection

The maps below highlight the links between voting and environmental justice. Click on a congressional district to see where it ranks nationally in each of three metrics: air toxin exposure, exposure inequality (the gap between the most and least exposed areas in the district), and socioeconomic distress. An explanation of these metrics can be found below the maps.

The metrics behind the maps

Median air toxin exposure for congressional districts and inequality of exposure within districts are measured using the Environmental Protection Agency’s Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators model for the year 2010. The model includes air releases of more than 400 chemicals from more than 15,000 industrial facilities. Data are provided by the Institute for New Economic Thinking: Boyce, J.K., M. Ash, and K. Zwickl. 2014. Three measures of environmental inequality. New York: Institute for New Economic Thinking.

The socioeconomic distress index is based on the Economic Innovation Group’s 2017 Distressed Communities Index, a composite index of economic and social conditions by congressional district, based on change in employment, change in the number of business establishments, education, housing vacancy, median income, poverty rate, and unemployment.

The voting convenience index combines data on voting eligibility restrictions—such as felon disenfranchisement and early registration deadlines—with voting process barriers such as ID requirements and restrictions on early and weekend voting.

The link between environmental justice and voting

A large body of research has shown that people of color and those living in poverty are more likely to live in communities with disproportionately high pollution exposure. And for a variety of reasons—such as cost, health, and the well-documented fact that voting is a habitual behavior—these EJ communities tend to have lower electoral participation.

In recent years, restrictive voting laws have been added to the factors that tend to depress turnout in EJ communities. A string of recent Supreme Court decisions has accelerated this trend by refusing to limit gerrymandering, freeing states from the obligation to clear electoral rule changes with the Department of Justice under the Voting Rights Act, and upholding restrictive voter purging.

As protections have weakened, some states have been quick to pass new laws that create barriers to voting, either by restricting voter eligibility, making the voting process more difficult, or shaping the rules for converting votes into electoral outcomes in a way that distorts representation and lowers incentives to participate. In many cases these initiatives can be traced to some of the same organizations, such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), that have been active in promoting climate change disinformation and blocking environmental regulations.

What our analysis found

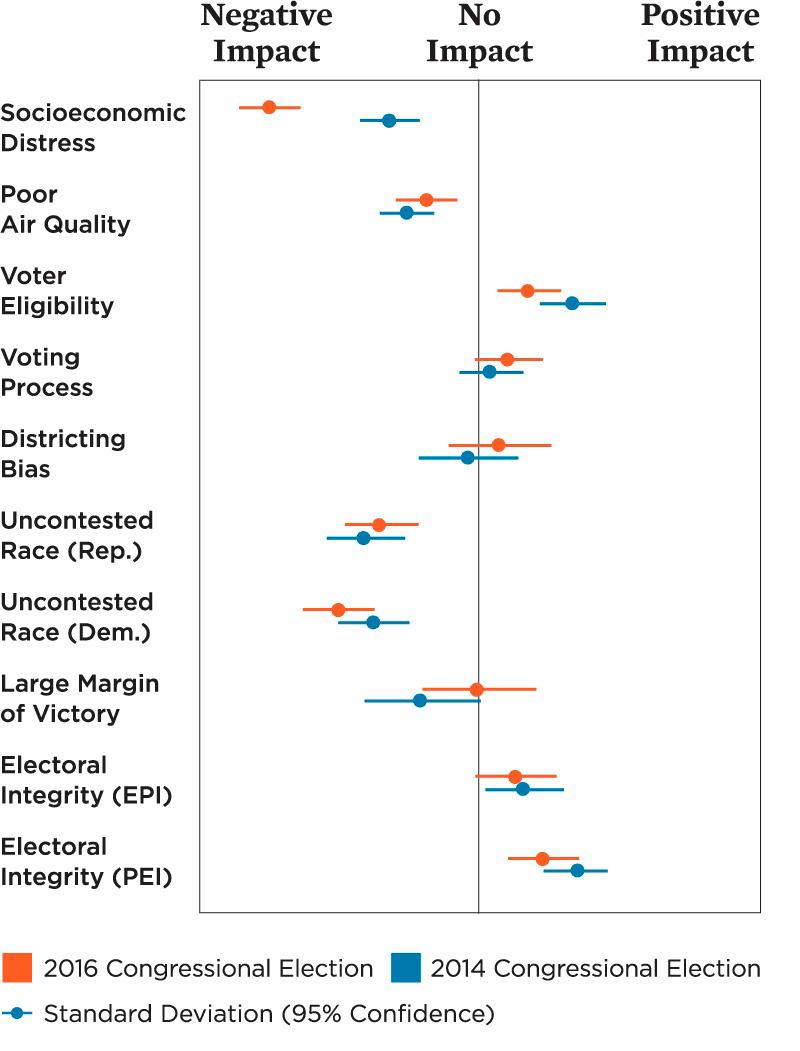

We analyzed the impact on voter turnout of a variety of socioeconomic, environmental, and political factors, using data from the 2014 and 2016 congressional elections. (For a full explanation of methods and data sources, see the report document.)

Socioeconomic distress, as measured by the Economic Innovation Group's 2017 Distressed Communities Index, was the single largest factor influencing turnout, particularly in the 2016 election (suggesting that the increase in turnout normally seen in presidential election years is concentrated within more affluent districts). Air quality also had a major impact.

Among electoral process factors, the largest impacts resulted from voter eligibility and partisan competition. Measures to broaden eligibility, such as later registration deadlines or same-day registration, could significantly increase turnout. While gerrymandering did not have a direct impact on turnout, the analysis did reveal a connection between gerrymandering and lower air quality, suggesting that gerrymandered legislatures are more likely to be responsive to the interests of powerful elites rather than the communities they represent.

Upgrading the tools of democracy: a suite of reforms

Every state can improve its electoral ecosystem, although some are more advanced than others. The evidence-based reforms below can expand the electorate, provide ease of access to the ballot, and make redistricting and elections fairer—and in turn, they'll give EJ communities a fighting chance of acting effectively to protect their health and safety.

Automatic voter registration: When citizens complete certain government tasks, like applying for or renewing a drivers’ license, they are automatically registered to vote unless they opt out.

Same-day registration: Citizens can register to vote up to and including election day.

No-excuse absentee voting: Registered voters can fill out an absentee ballot without falling under a limited category of excuses. Many states unnecessarily restrict access to absentee ballots. For example, first-time voters in Virginia who are first responders or have a religious obligation cannot vote absentee.

Early in-person voting: Eligible voters can vote in-person before election day, including weekends.

Felon enfranchisement: All citizens automatically receive the right to vote after being released from prison.

Student ID as voter ID: Permit student identification cards to count as voter ID in states where there is an ID requirement.

Online voter registration: Allow voters to register online.

Independent redistricting: Appoint an independent commission to draw legislative districts.

Ranked-choice voting: Voters rank candidates in terms of preference. If a candidate fails to reach 50% of the vote, votes are reassigned to voters' second-choice candidates until one candidate has a majority.

Multi-member districts with preferential voting: Multiple candidates are elected from a single district; this system is used to elect state legislators in 10 states, but they do not yet use preferential formulas like ranked-choice voting. Together these reforms ensure a more accurate representation of public support for political parties, while creating more competition between political parties.

November ballot actions

Many citizens, seeing inaction in their state legislatures, have taken matters into their own hands. Five states have voter rights initiatives or constitutional amendments on the ballot in November. We support all eight common-sense reforms, which would reduce partisan influence on drawing legislative districts, and increase access to the ballot.

- In Colorado, Amendment Y (the Independent Commission for Congressional Redistricting Amendment) would create a 12-member commission of four Democrats, four Republicans, and four independents to draw congressional districts. The plan would have to consider electoral competitiveness in creating the districts. Eight commission members, including two independents, as well as the Colorado Supreme Court, would need to sign off on the plan, which could not be vetoed by the governor.

- Also in Colorado, Amendment Z (the Independent Commission for State Legislative Redistricting Amendment) would create a 12-member commission of four Democrats, four Republicans, and four independents to draw state legislative districts. The plan would have to consider electoral competitiveness in creating the districts. Eight commission members, including two independents, as well as the Colorado Supreme Court, would need to sign off on the plan, which could not be vetoed by the governor.

- In Nevada, the Automatic Voter Registration via DMV Initiative would automatically register eligible citizens to vote when receiving some services from the DMV, such as obtaining a drivers' license.

- In Florida, the Voting Rights Restoration for Felons Initiative would restore the voting rights of people with prior felony convictions after completing parole or probation, except those convicted or murder or sexual offenses, who would have to petition the governor on a case-by-case basis.

- In Utah, the Independent Redistricting Commission Initiative would create a seven-person bipartisan commission to draw state legislature and congressional districts. Five commission members, as well as the Chief Justice of the Utah Supreme Court and the state legislature, must sign off on the boundaries.

- In Missouri, the Clean Missouri Initiative would give redistricting power to a nonpartisan expert, open legislative records to the public, prohibit lobbyist gifts over $5 in the state legislature, bar politicians from lobbying until two years after their term expires, prohibit political fundraising on state property, and reduce the maximum campaign donation.

- In Michigan, the Independent Citizens Redistricting Initiative would create a 13-person bipartisan committee to draw state legislature and congressional districts. Committee members will be randomly selected from two separate application pools and cannot serve if they have any number of conflicts of interest, such as recently running for office, working as a lobbyist, or having a family member work for a state politician.

- Also in Michigan, the Promote the Vote Initiative would eliminate voter registration deadlines, provide access to absentee ballots for all, protect the right to a secret ballot, mail absentee ballots to military service members 45 days before elections, re-introduce straight ticket voting, and audit election results.

Unfortunately, two state legislatures have referred to the ballot two voter ID amendments that could suppress thousands of eligible citizens. Voter ID laws disproportionately affect minority voters, senior citizens, low-income voters, and young people.

- In Arkansas, Issue 2 (the Voter ID Amendment) would require individuals to present valid photo ID to vote in-person and absentee. The state legislature would determine after the fact which identification is considered valid.

- In North Carolina, the Voter ID Amendment would require individuals to present valid photo ID to vote at the polls. The state legislature would determine after the fact which identification is considered valid.