Climate-related transportation policies have enjoyed relative success in the United States.

After years of stagnation, federal fuel economy standards were passed in 2011, increasing the efficiency of new cars and trucks. Advanced new cellulosic ethanol plants are finally ramping up, churning out low-carbon alternatives to gasoline. And more electric vehicles are on the road now than ever before.

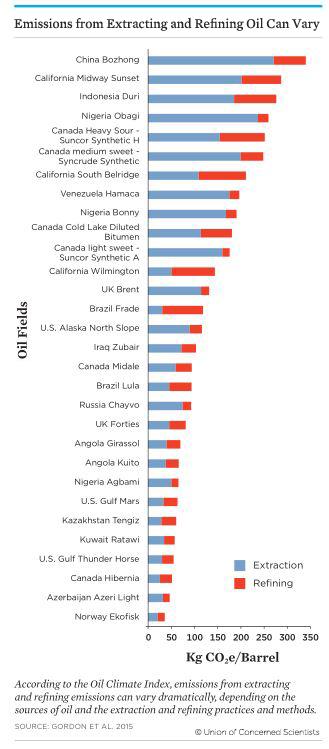

But there is a largely unrecognized problem undermining these efforts, the oil we use is getting dirtier. The resources broadly described as oil are changing, with major climate implications. The global warming pollution associated with extracting and refining a barrel of oil can vary by a factor of more than five: from less than 50 kilograms of carbon emissions per barrel to more than 250 kilograms. These emissions represent a small share of gasoline’s total climate impact, but it’s an important one: given the global scale of oil consumption, even slight increases in oil-related emissions can have dramatic—and disastrous—consequences.

These added emissions occur as companies exploit hard-to-reach oil resources, which require extra energy to extract and refine. Instead of minimizing their climate impact, the oil industry is ramping up production of unconventional oil, wasting significant amounts of energy and contributing to the climate crisis in avoidable ways.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Smart policy choices can help ensure biofuels and electricity continue getting cleaner, while also holding oil companies accountable for unnecessarily dirty practices.

Oils aren’t created equal

Most drivers think of gasoline as generally uniform, “more or less the same everywhere.” But hidden behind the gas pump is a global oil supply chain that is changing in profound and damaging ways. Inexpensive and easily-accessed oil reservoirs are drying up, forcing major industry players to locate, extract, and refine ever-riskier, costlier, and dirtier sources of oil.

These unconventional sources include Canada’s tar sands, an oil with the consistency of peanut butter that requires massive amounts of energy to extract and refine into useable products. Tight oil is another major culprit: located throughout the United States, tight oil wells require fracking and also produce methane, a potent greenhouse gas that, instead of being captured and used, is often vented or burned (“flared”).

Thanks to these and other unconventional oils, the pollution associated with extracting and refining a barrel of oil has steadily risen. Should extraction and refining processes continue getting dirtier, production-related emissions could increase by a billion tons or more over the next 20 years—an amount roughly equivalent to the tailpipe emissions of all U.S. cars in 2014.

Progress with alternative fuels

The oil industry’s failure to decrease emissions has occurred against a backdrop of progress by electric cars and advanced, next-generation biofuels. Two-thirds of all Americans now live in areas where driving an electric car produces fewer climate emissions than almost all comparable gasoline and gasoline hybrid cars—a fact attributable to more efficient vehicles and an increasingly clean electricity grid.

Meanwhile, biofuels have grown exponentially, with ethanol now accounting for 10 percent of all gasoline. Most ethanol today comes from corn, which is around 20 percent cleaner than gasoline but which competes with food crops and forests and is also linked to water pollution (PDF). Fortunately, advanced biofuels made from non-food resources are steadily leaving the laboratory and contributing to the low-carbon fuel supply—offering huge potential to cut oil use.

Oil industry’s role

Like everyone else, oil companies have a responsibility to reduce the emissions from their own operations, even as the transportation sector uses less and less oil. The common practice of flaring natural gas, for example, is wasteful and unnecessary, and is the product of a flawed regulatory system rather than an inherent property of the oil. And some of the dirtiest fossil fuels (like tar sands) could be avoided in favor of less-polluting resources.

Transparency is also needed. We know more about ethanol than we do about the oil that makes up 90 percent of gasoline. Disclosure laws requiring oil companies to reveal the carbon intensity of their fuels are sorely needed, as are policies to reduce those emissions. Only California and Oregon have such laws on the books today.

Not standing in the way of rigorous climate science and climate policy is just as important. Despite producing a disproportionate share of the world’s carbon emissions, most of the world’s largest oil and gas companies are or have been involved with climate deception and disinformation tactics. Denying established climate science is unacceptable and unhelpful.

Ultimately, we need to use less oil—a lot less. Fuel efficiency, electrification, and cleaner, low-carbon fuels can help us get there, while a better-managed and more responsible oil industry could ensure what oil we do use doesn’t get dirtier.

Download the report or executive summary for an in-depth analysis of transportation fuels and their role in combating climate change. See the technical appendix for a detailed explanation of key calculations, or download the chapters seperately on oil, biofuels, and electricity.