Classical breeding—the practice of improving crop varieties by selectively breeding the best-performing plants—can help farmers increase their yields and profits, battle pests and weeds, resist drought, adapt to changing climate conditions, and enhance sustainability and global food security.

Decades of research and experience show that the technology of classical plant breeding is effective and efficient, achieving its goals at a fraction of the cost of genetic engineering. But the few remaining publicly funded classical breeding programs, found in our nation’s farms, universities, and agricultural research centers, are starved for resources. As these programs decline, the development of new crop varieties is increasingly driven by corporate market shares and profit margins rather than by the needs of farmers.

This situation needs to change, and our 2015 fact sheet, Seeds of the Future, makes the case for changing it.

Classical breeding: a proven technology

Classical breeding is responsible for the majority of existing crop varieties, or cultivars, around the world. Using technologically advanced methods, including analysis of genetic makeup, an improved cultivar can be produced in only a few generations of breeding. This is a relatively low-cost process, and it delivers traits that meet the needs of today’s farmers, such as:

- Tolerance to drought and other adverse climatic conditions.

- Resistance to disease and pests.

- Productivity.

- Efficient use of nutrients such as nitrogen fertilizers.

- Adaptation to local growing conditions.

- Profitability, through breeding for multiple desired traits in a single cultivar.

- Adaptation to organic farming and other regenerative systems.

The current crisis in plant breeding

Despite the proven benefits of classical plant breeding, publicly funded programs that could produce the seeds of the future have been in decline for decades. Recent studies have found that classical breeding programs have shrunk by more than 30 percent over the past 20 years. Even widely grown crops have few remaining public breeders.

Overall, public investment in our nation’s land grant universities is declining relative to private investment, shifting research priorities from the broad public good toward the relatively narrow interests of agribusiness.

The decline of public breeding programs has resulted in an overreliance on a few genetic lines for some major crops. This threatens our nation’s food security because low genetic diversity makes it easier for crop diseases to spread quickly and widely.

Improving sustainability with classical breeding

Publicly funded breeding programs are crucial to the development of sustainable farming systems. Agroecology—the application of ecological principles to farming—is the science most relevant to some of agriculture’s biggest challenges. Agroecological approaches aim to manage whole systems by simultaneously sustaining crop and livestock productivity, efficiently recycling inputs, and building natural capital—such as soil fertility—while reducing harmful impacts on soil, air, water, wildlife, and human health.

However, agroecological approaches can have maximal effect only when appropriate cultivars are available. And classical breeding is much better suited than genetic engineering techniques to developing the cultivars needed for agroecological systems. Classically bred cultivars generally cost less to develop, and can be tailored to the specific needs of diversified and sustainable farming systems.

Recommendations

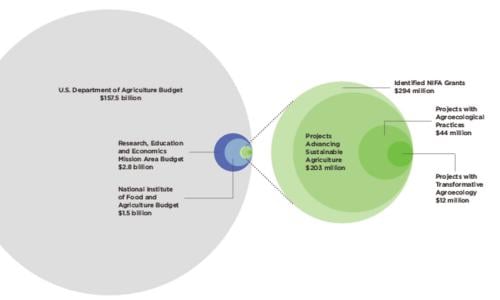

- Public research funding for classical breeding, especially for agroecological systems, should be sustained and increased. The appropriate lead agency, with the mission and capacity to support this effort, is the National Institute for Food and Agriculture of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

- Development of publicly available cultivars suited to agroecological systems should be a distinct and high-priority category in USDA competitive research grant programs.

- Because field breeding programs tend to run on a 15-year cycle—the typical amount of time needed to produce new cultivars, regardless of the technologies used—policy makers should focus on sustained long-term investments.